Are you aware of how you

sound to others when you are talking?

I was on the phone in my Tesla yesterday, sitting in the grocery store's lot, talking to a close friend about a mutual friend struggling with a personal problem I have struggled with in the past. At one point in the conversation, I noticed that I was leaning forward, my forehead almost touching the top of the steering wheel, and my voice had grown loud and insistent.

I realized I was triggered and that my energy had increased by 2,000 degrees.

The good thing is that I am now more aware of when I enter a verbal trance such as this. I can catch myself by hearing my voice and make a more conscious decision about how I want my words and voice to come across rather than having the other person listening be a victim of whatever the lower dark cauldrons of my brain decide to spit out of my mouth.

The tone, pitch, and cadence of our voices convey a massive amount of information to others. In other words, it's not what you say but how you say it that most often determines the message the listener hears.

Albert Mehrabian, an emeritus professor of psychology at UCLA, estimates how we say something accounts for 38% of our message, with body language coming in at 55% and the actual words themselves a measly 7%.

As I learned in the incredible speaking program Heroic Public Speaking, the way we say I love you can convey a plethora of different meanings: an expression of passion, doubt, reassurance, a question, or a proclamation. The tone, pitch, and cadence of delivery are called information contours, and these information contours transmit a ton of information about what the words mean to the person speaking them.

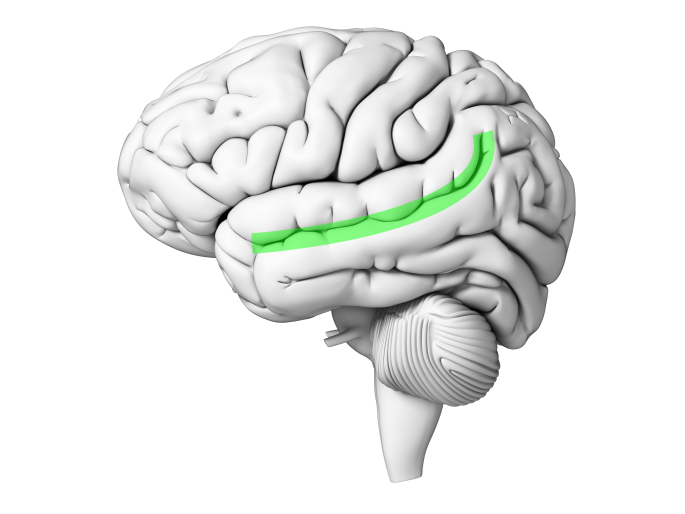

We can quickly become more aware of our body language and, of course, the words we choose, but we are tone-deaf about becoming more aware of how we sound when speaking. And there is a good reason for that: our brain's superior temporal sulcus (STS).

In infants, the STS is the riverbed upon which flows all of what the infant hears. But by 7 months, the riverbed gets persnickety and will now only let in human voices. That's it—just human voices. But what really activates the STS is when those voices carry emotion. The STS is dedicated to taking in language and reading tone and meaning.

But get a load of this: when we ourselves speak, the STS turns off. We do not hear our voice like everyone who is listening to us babble hears our voice. What we hear are just the words tumbling out of our mouths. Everyone listening hears the words and the tone, pitch, and cadence of our words. We only hear the words.

How many times has someone said to you, " Don't use that tone with me," or "Why are you angry?" and you are like, "WTF are you talking about? "I didn't use that tone," or "I'm not angry!"

This STS business is also why our voices sound weird and unfamiliar when we hear them on a recording. Sophie Scott from the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience thinks this is because our brains can only focus on one thing at a time (sorry, multitasker believers), so we (the speaker) naturally focus on the intentions behind the words and not on the energy (or tone, pitch, and cadence) of their delivery.

Once I learned about this STS glitch, I have tried to be more aware of how I am saying something. It is not easy because when I am engaged in thinking about a topic and the words are just bubbling up from the cauldron of my neurologic jungle, I am often in sort of a spell or movie. One of the most valuable skills I have learned (thanks again Sam Harris) is the ability to step out of the movie running in my head and see and smell the popcorn in my lap.

One of my challenges (present for as long as I can recall) is getting very intense when I am passionate about a topic. This manifests as a somewhat deeper tone, raised voice (pitch), and much faster speaking rate (cadence). Sometimes, the intensity and energy are incredibly valuable. Other times, they can be alienating and shut down the conversation.

I prefer to have more choice in my words' tone, pitch, and cadence.

As someone says, awareness is the first step. So, I started to pay more attention to catching myself when I get activated or triggered and then pause in my head to think about how I want to deliver my message.

This is an incredibly important skill in the wilds of civilization and work, where how you say things can matter a great deal in terms of how people relate to you and to your reputation.

But it is also critical, perhaps even more so, at home with our loved ones. When we walk in the door, free of the shackles of the outside world's expectations, we can get lazy and say things in a way that, over time, can start a slow downward spiral that can profoundly damage a relationship.

Being aware of how our voice comes across with our loved ones is, in my opinion, as important as showing gratitude and constant signals of belonging, as the book The Culture Code by Dan Coyle so well demonstrates.

However, awareness of how we sound can be elevated to an epic level by learning how to intentionally use tone, pitch, and cadence to convey our message in a way that inspires and influences people instead of just speaking in our usual self-tone-deaf way. To learn more, check out this video with Vinh Giang, an incredible communication guru.