"Just An Addict"

A few months after I was discharged in May 2012 from my three-month stint (incarceration) in Hazelden rehab center for prescription narcotic addiction, a friend and surgical colleague from the University of Minnesota actually reached out and asked if we could have lunch!

I italicized and used the word actually and the exclamation point because, unlike when you are sick, and people send cards or call to see how you are and if they can help, when you struggle with addiction, very few people know how to approach the situation (and boy do I get it), or they've put you in the human trash bin of being a "just an addict." Either way, it only exponentially magnifies the horrifying levels of shame you already feel for being an "addict."

But get this: my friend and I came from different planets. He grew up in the Mormon faith and still has a deep commitment to it. He is a calm, kind, and very thoughtful man.

Whereas I was, to quote another surgeon, "a force to be reckoned with" - a wildly extroverted, energetic, and intense man who came from a dreadful personal childhood devoid of any structure (well, it had a structure, but not an ideal one).

My friend and I worked together on many projects over the years, so we gradually came to know, like, and respect each other despite being totally like Felix and Oscar in the TV series The Odd Couple.

The day we met for lunch at Chipotle, I gave him a hug (I was so happy to see him), and we ordered our burritos and sat down to catch up. I pulled the foil wrapper down halfway on the burrito and was chomping away as he was filling me in about changes in the surgery department and what was going on with some of our mutual colleagues when, almost in passing, he mentioned how a colleague had recently referred to me - "Maddaus is just an addict."

I felt the razor-sharp knife of shame stab me in the gut as my "failure" washed over my entire being yet again.

This colleague was well-known to be difficult and judgmental, which is why I am sure my friend discounted the "just an addict" comment as not surprising.

Well, it wasn't surprising to me, but it still hurt, a lot, because shame is one of the most potent and potentially destructive emotions we humans have to deal with.

Shame is the air you breathe when you are addicted to something.

Shame for being "weak" and not being able to just stop the drug or whatever the thing is that has its hooks into you.

Shame for violating your values and morals as you sink deeper and deeper into the abyss.

Shame for the impact of the addiction on your family, loved ones, friends, and colleagues.

Shame for being a f@*^ing loser.

A side note on shame vs guilt. Guilt is what we feel when we do or say something specific that we feel bad about; the target of our guilt is the specific act or transgression, which means there is an opportunity for psychological relief, healing, and reconciliation with an apology or restitution.

Unlike guilt, shame is a feeling of not being worthy as a human being (either in reality or in our imagination) in the eyes of other people, especially by people whom we value, such as family or colleagues.

Shame is one seriously potent and potentially destructive emotion, and for good reason. As hunter–gatherers, our survival depended on cooperative interactions to avoid starvation and death. If one person was a problem for the tribe and the mission of survival, they were ostracized, which back in those days amounted to a death sentence. Shame is the emotion that evolved to keep us in line with the tribe, so we could survive.

So I've got serious shame for just being an addict for all the reasons listed above. But then came a moment in time that ignited a raging fire of shame that is forever burned into my memory.

I was in a conference at work when I got called up to the chair's office - I was to report "immediately."

Fear coursed through my veins as I took the elevator to the 11th floor and sat in the outer office of the boss's office. After what seemed like an eternity, the door opened, and I was called in. The chair and vice-chair (a friend and someone I had known since residency) were sitting at the conference table. I sat down and they told me that my partner (thank God) had told them about my struggle with narcotics and that I was to leave work immediately and report to Health Professional Services Program.

That was it. Straightforward. Leave now.

I got up, walked out, took the elevator down to the ground level, and as I walked down the hall to the exit, I walked by the CEO of our practice plan, a physician colleague whom I had known for over 20 years and who I considered a friend. She looked over at me, at my face and eyes, and immediately averted her gaze and kept walking right by me, pretending not to have seen me.

Let's just say that when I got into my car in the ramp that day in the middle of February when the temperature was -10 and the skies were dark grey.........

I made it through that moment and barely made it through the next 10 days as my house of cards unraveled completely. Finally, I capitulated and decided to go to Hazelden.

It's hard to admit, but I was like the author Stephen King when he was addicted to all manner of substances. His family staged an intervention, during which he tried to convince them to just give him a couple more weeks, and he would get off the shit.

King wrote that his refusal to go into treatment was like being stuck on the roof of a burning skyscraper and there is a helicopter overhead that has unfurled a ladder to rescue you, and as the flames are shooting out of the windows just below and the roof is heating up you yell up at the helicopter; "thanks but nah, I can manage."

To this day, I cannot believe how screwed up my thinking had become.

So that's how Michael Maddaus, who is "just an addict," ended up being driven north of Minneapolis to Hazelden one bitterly cold and sunny early March morning by 3 of his kids and dropped off in the reception lobby - drowning in a sea of melancholy - while being given reserved but caring hugs and I love you's from his kids and who then, with the receptionist standing and waiting behind him, watched his kids walk out and drive off in his car to go back home, without him.

About 10 days later, after going through a withdrawal nightmare, I found myself in a group session when it became clear to me that I had to fall into line with the rest of my fellow travelers (addicts) and do as I was told; to introduce myself as "Michael, addict" in the group, and apparently for the rest of my life.

The word addict is a noun. A label. I get why they insist on this, so you never forget. Whether or not this is the right move (I don't think it is), any label put on someone moves the more challenging work of understanding the complexity of a human being and all the forces acting on their lives off to the side in favor of a simple, tidy label and explanation of another person. It's cognitive laziness.

That wildly difficult moment in the lobby of Hazelden (like most moments in life) came to be, not because I was weak, but because I was slowly weakened in a slow downward spiral by a multitude of nearly invisible forces that I had no real understanding of.

The Learning Retrospectoscope lesson (that took me several years to figure out) is this: like most moments of "bad" behavior or "bad" decisions (and they sure as hell may really be bad behavior or decisions), the bad behavior or decision is but a sliver of the concatenation of events that have piled up over time that led to that moment and that bad behavior or decision. This is true of every snapshot of anyone at any moment. Every moment in time is an accretion of forces and events that culminate in that moment.

This fact offers a mental pathway to toss the judgments and rigid thinking out the hatch so you can land your mind in an open field of understanding and compassion. This by no means means that you accept or tolerate the bad decisions or behavior. It means understanding, which can open the door to connection and change.

I like to think of the process as being like a root cause analysis, which is performed after airplane safety incidents.

In an aviation root cause analysis, the investigation starts with the premise that the pilots did not intend to do harm, the direct opposite of the powerful cultural sense of individual accountability and fault finding that persists to this day in the world of surgery and medicine, and with so many of our fellow human beings.

So, if you are willing, read along, and I hope with the premise that I did not intend to do harm, which is true.

So, in the case of my addiction, the symptoms are me ending up in Hazelden in a physical, emotional, and spiritual mess. The problem is the addiction to narcotics. It is the causes or the whys that led to the problem of addiction that I want to focus on here.

Why #1 - High Adverse Childhood Events (ACE) Score 7/10

That is me on the left, blissfully unaware of the world I would face. My mother, Lorraine, is in the middle. She was a waitress, I was born out of wedlock (she had an affair with her boss, a married man with three kids), as an only child, we were poor as hell, and she became an alcoholic. The pattern was drinking till bedridden and not eating and near starvation, off to the hospital, then back home to "normal" mom for 3-6 months, then rinse and repeat, with an occasional hellish suicide attempt thrown in. My "stepfather," Ralph, a violent and brutish man, is on the right.

Here's one of the highlights of my teen years: I came home after school in the afternoon, opened the door to our small apartment, and I immediately knew something was dreadfully wrong. The shades on all the windows were down, and there was only one dim yellow light on in the corner of the living room. It was as quiet and still as an empty church at night, until I heard my mother sobbing. I walked into the dining room and found her sitting in a chair, dressed only in her panties, drunk and hardly able to sit up, holding a razor blade in her right hand, and trying to cut her left wrist. Blood was all over her and the dining room table.

I start yelling at her to stop and grab the razor blade when suddenly Ralph walks in with a bag of groceries in each arm. I'm yelling and screaming at her and now at him. Ralph just lets the bags of groceries fall onto the floor, brings his right arm across his chest, and lets loose a fist-clenched backhand on my face that knocks me across the room and onto the floor.

What's interesting, at least to me, is that I have zero recollection of anything after getting smacked and lying on the floor with my hand on the side of my face. I am sure I got up and ran out and probably stayed out all night somewhere. But I don't remember anything else about the event or the days after. If you think about it, it was probably pretty "awkward" around "home" for at least a few days after, but I just don't remember any of it.

So, no surprise that I end up on the streets with my delinquent friends (the other "losers" from school) and in relentless trouble with the law; arrested 24 times and in and out of reform school 5 times. Every single day was another challenge and trial to get through.

A way of measuring the impact of abuse on a child is to look at their ACE score (Adverse Childhood Events), which is a tally of the different types of abuse, neglect, and other hallmarks of a rough childhood. The higher the score, the higher the risk for negative life outcomes, like markedly poor health and addiction. My ACE score is 7 out of a possible 10 points, putting me in the very high risk category.

Why # 2 - The Hidden Surgical Curriculum

During surgical residency, the primary goals are to learn how to take care of patients and operate. It is, without question, a career that demands very high performance.

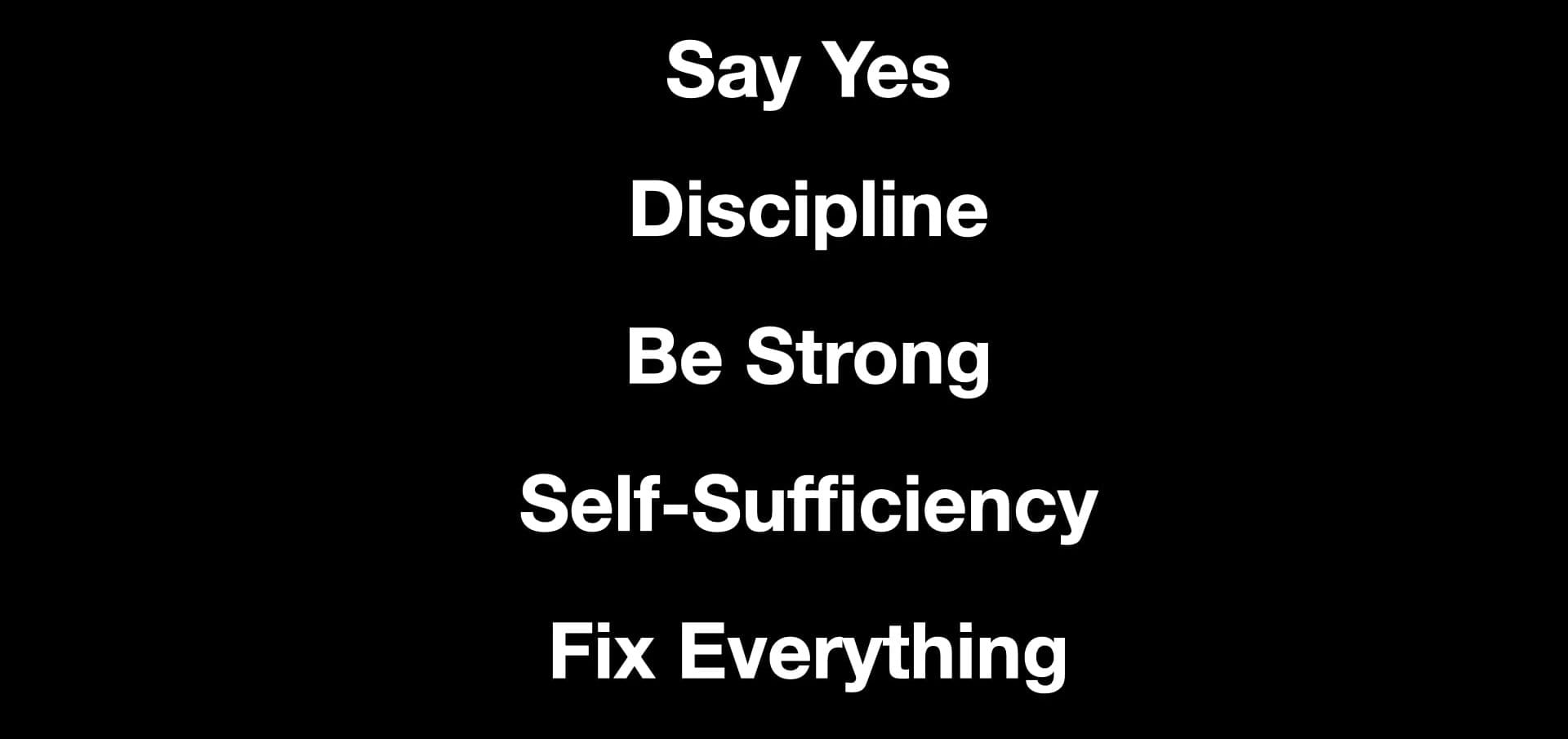

Though not explicit, there is a hidden surgical curriculum that inculcates us with 5 habits through cultural osmosis.

The Say Yes Habit. As a resident, you say yes like a good soldier to any and all requests made by authority figures. All fine and good while you're a resident, but the carryover into the career stage leads to doing a lot of things you can't stand, to a lack of fulfillment, to chronic busyness and overwhelm, and burnout.

The Discipline Habit. A critical skill to learn so you can step up to the plate no matter how you feel and get the job done.

The Be Strong Habit. Surgeons are human beings, and they have emotions and setbacks and struggles - personal and professional - like all human beings. We learn to pretend we are ok even when we are not, one of the grandest forms of emotional labor ever.

The Self-Sufficiency Habit. This one is deeply intertwined with the Marlboro Man and American rugged individuality. We have strayed profoundly from the profound biological need we all have for mutual support and belonging, and we feel weak if we are lonely or need real help.

The Fix Everything Habit. Surgeons are sensational at looking at a problem with detachment, planning out a way to solve it, and then executing. The problem is that not every problem needs fixing. Sometimes, we have to simply accept reality, as with a personal loss or with significant life changes. In these circumstances, the attempt to fix just makes the issue go underground in your neurologic cauldron, only to rear its head later, when the cauldron starts to boil.

Why # 3 - Lonely

"The quality of your life depends on the quality of your relationships." Esther Pearl

My wife Lea is (now retired) a high-risk obstetrician. She routinely took in-house call 5-6 nights a month for years and worked the next day after call, all while fully supporting my career and managing all the kids.

Combine this with my constant working, and it's no surprise that our relationship underwent a slow downward spiral into one of more and more transactionality. In many ways, we became like ships passing in the night. In bed, she’s just a foot away, but she might as well be in another bedroom. I missed her, I missed us, but the gulf between us seemed so vast that I had no idea where to even start to fix it all.

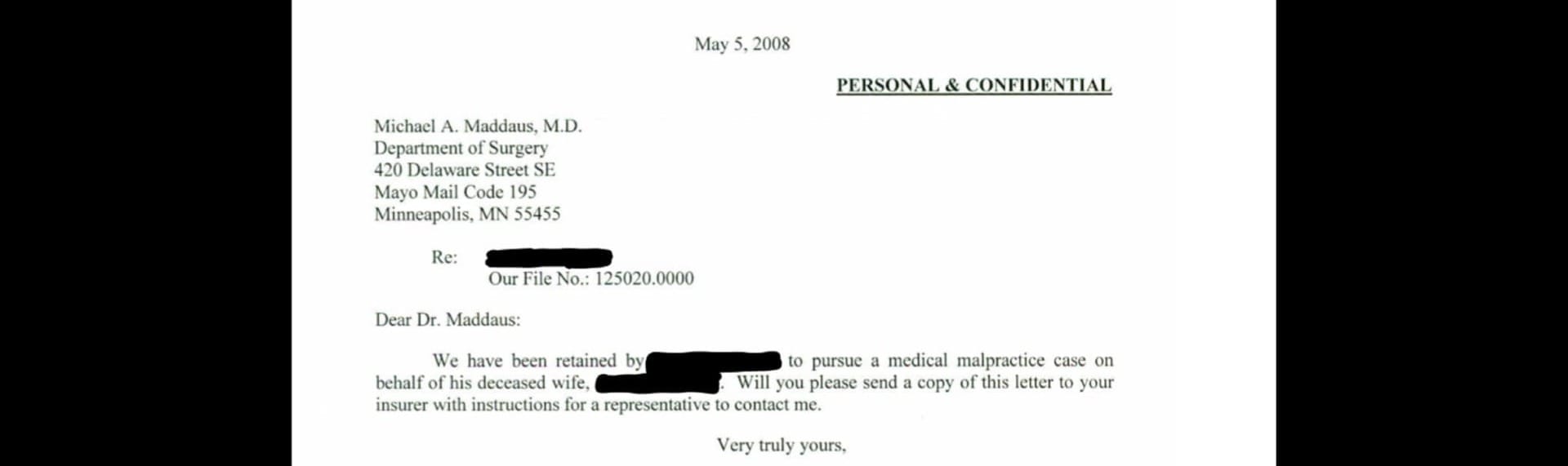

Why # 4 - Intraoperative Death and Lawsuit

Four years before my first bottle of 360 narcotic tablets, I had a tragic intraoperative death on the table. The patient was young and had benign (not cancer) disease. I hadn't done anything wrong, but I was sued, and after over a year of legal struggles, they dropped the lawsuit. The death, more than anything (and still does to this day), but also the lawsuit, haunted me nearly every day after, adding fuel to the eventual slow downward spiral.

Why # 4 - Lack of Fulfillment at Work

My yes habit, so necessary at the beginning of one's career to experiment, contribute, and learn and grow, carried on full steam throughout my 20-year career. This is a problem I see over and over with surgeons I coach - the failure to winnow down the things they are doing to only the things that bring fulfillment and energy, and to those things that are necessary to be a contributing citizen and to support your career.

It is still a bit embarrassing to admit, but once I had mastered a surgical procedure (and I was an exceptional technical surgeon - no hubris, just knowledge that I was really good at operating) I felt bored and anxious that the rest of my career would be spent grinding through hundreds more of the same procedures.

I loved the complex and multifaceted process of mastering an operation until it became second nature. At a more meta level, I love the generic process of breaking down a complex issue or problem, deeply analyzing and understanding it, separating it into its component parts, and then teaching them to other people (obviously, that is what is going on here!). As my wife Lea said one time (and she didn't mean it as a compliment): "You're not happy unless you have a problem to solve."

I do believe that if I had learned to use the word no, combined with a richer understanding of my unique strengths and drivers, I may have stemmed the slide into just doing, doing, doing as the default protocol, and the generalized misery that brings.

Why # 5 - Had to Stop Running

This is the straw that broke the camel's back. I had struggled with lower back pain and disk troubles for years, but the pain escalated, and I started to have severe bilateral radicular leg pain.

Running and exercise in general have been a staple of my existence ever since I was 21, and it has been my main way of managing stress, and now the door on that seemed to be closing in on me, too.

One day after a run I was bent over in front of our house in pain and in that moment I realized that I would never be able to run again. I pulled out the fix-everything habit, contacted a famous spine surgeon that I know, and he recommended proceeding with a five-level lumbar fusion since I had such severe osteoarthritis and disk disease with some scoliosis.

So I flew out to Los Angeles and had a five-level fusion. It was categorically the worst physical thing I have ever been through in my life. In 8 weeks, I managed to get back to work off narcotics, but one day, after a long operation, I could hardly walk.

Turns out, unbeknownst to me, both hips were bone-on-bone. I couldn't bear the thought of more surgery, so I saw a pain anesthesia colleague at work who injected them without relief, so he wrote me my first prescription for 360 narcotic pills. Refills were whenever I needed them, all without having to even go to clinic.

So there you have it, a Root Cause Analysis of the problem of addiction in Michael Maddaus. The benefits of understanding myself have been valuable from multiple perspectives for me:

- It allowed me to begin to forgive myself for the entire mess, because believe me, I was so hard on myself for the addiction and the "choices" I made and their impacts on everyone around me.

- Forgive, yes, but forget, no. Once I got through the hell of getting off the drugs and getting past the horrible shame of what I did and what the impact was on my family and colleagues, I knew that I would never allow this to happen to me again. I could not voice this because anyone reasonable would be like - "yeah sure Michael, heard that before," but I meant it then, and I mean it now. It is my responsibility, because I now understand the peril and know the consequences.

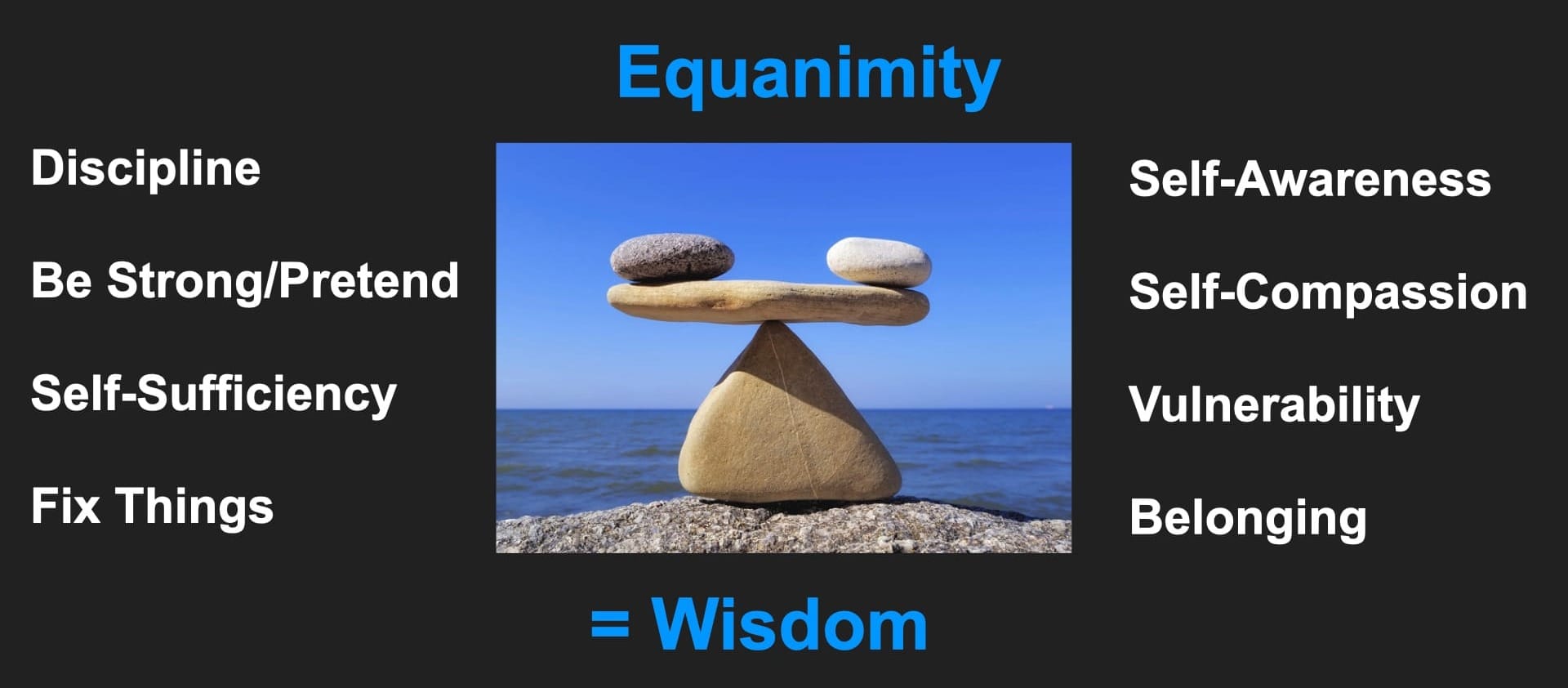

- Equanimity in our approach to living. I love the 4 of the habits of surgeons: discipline, self-sufficiency, be strong, and fix everything. They are superpowers that, when deployed with discernment, can move mountains. But like I've said again and again (and will almost certainly continue to say), they are good until they aren't. They need to be balanced with our humanity and with the other superpower habits of self-awareness, self-compassion, vulnerability, and belonging.

The ability to toggle between the two realms, and to know when and under what circumstances, is the land of wisdom.

I am reading a great book at the moment called Your Next Conversation by the attorney Jefferson Fisher, and in the first chapter, he writes:

“The person you see is not the person you are talking to.”

Jefferson notes that each human being is like a river with an undercurrent. The surface things - the cues you pick up with your eyes and ears shape your perceptions and judgments about them, but it is what is below the surface where the real truth is.

“The coworker you see is agitated and impatient. She didn’t sleep well last night because she's worried about convincing her brother to go to rehab.”

“The cashier you see is scattered and inattentive because he's worried about affording his kids’ back-to-school supplies.”

There is an incredibly rich and vibrant world of cause and effect in all of our lives that is invisible to us, unless we get curious and look, intentionally. Being curious and interested in those deeper layers is part of what makes being a human being such a rich experience.

I wrap up with a quote from Bob Ginsberg, a renowned thoracic surgeon whom I was so fortunate to have as a teacher and mentor. One day on rounds, he told me, "If, in doubt, give the patient the benefit of the doubt." That one phrase profoundly impacted my practice and the outcomes of so many of my patients. It gave me an anchor to think more deeply about the problem and to move forward when I had doubts about the right clinical decision when the path was not crystal clear.

It's true in life, too, with our loved ones, our colleagues, our friends, and the cashiers who help us move through our days.

It's all about putting some perspective on your perceptions.

By doing so, you reap a profound mental health benefit: instead of the constriction of judgments and lack of understanding and being irritated, you have an expansive, humane state of mind, which is the potential superpower of being a human being.

So in that vein, I go back to my colleague at work who said "Maddaus is just an addict." That moment in time for him was, like all moments, but a sliver of the concatenation of events that have piled up over time that led to that moment.

If in doubt, give them the benefit of the doubt.

Bonus content! - a wonderful video I literally came across this morning.

Feedback with a thumbs up or down is greatly appreciated, or drop an email to me michael@michaelmaddaus.com.