My Mom, Lorraine

My Just an Addict post from April 2nd was a hard one for me to push send on for a few reasons.

- I still feel shame about the addiction. But the only way to diminish its power over me (or over any of us) is to bring it into the light of day. Two quotes from Brene Brown are apropos here:

"Shame loves secrecy. The most dangerous thing to do after a shaming experience is to hide or bury our story. When we bury our story, the shame metastasizes."

"If you put shame in a petri dish, it needs three ingredients to grow exponentially: secrecy, silence, and judgment. If you put the same amount of shame in the petri dish and douse it with empathy, it can't survive." - The two stories in there - about leaving work, and my mother Lorraine's suicide - are still tough for me, and I didn't want to cast a bad light on my colleagues at work or my mother. My colleagues were caught in a shitty situation with me, and my mother was caught in a shitty situation in life.

Which brings me to today's post, which is an attempt to do a post-mortem (literally) root cause analysis of my mother Lorraine's life, as I did with mine, in an effort to better understand her and the forces that led to her alcoholism and the suicide attempt.

One other thing. Lorraine's story is deeply intertwined with mine, so there will be a mixture of my efforts to see things from her perspective while also showing how my thinking and perspective on my mother evolved over time.

Lorraine's story starts with Peggy Amanda Olsen, her mother, and my grandmother.

Peggy was born in Kristiansund, Norway, on July 14th, 1895. Imagine living in Norway at that time.

For some reason, Peggy decides to leave Norway around 1917, when she is only 22 years old, by herself, on a ship across the Atlantic, to Ellis Island and then to Duluth, f*&%ing Minnesota!

I have no idea why she left, but when I visited Kristiansund with my daughter Maya in 2022, we learned that during Peggy's time, people were desperately poor. This is the trunk she brought with her on the boat, which I thankfully still have.

Shortly after arriving in Duluth, she married Hans Solie, my grandfather. Was it arranged, or did they know each other in Kristiansund? Perhaps she knew Hans in Norway and had planned to follow him to the United States after he got "set up?"

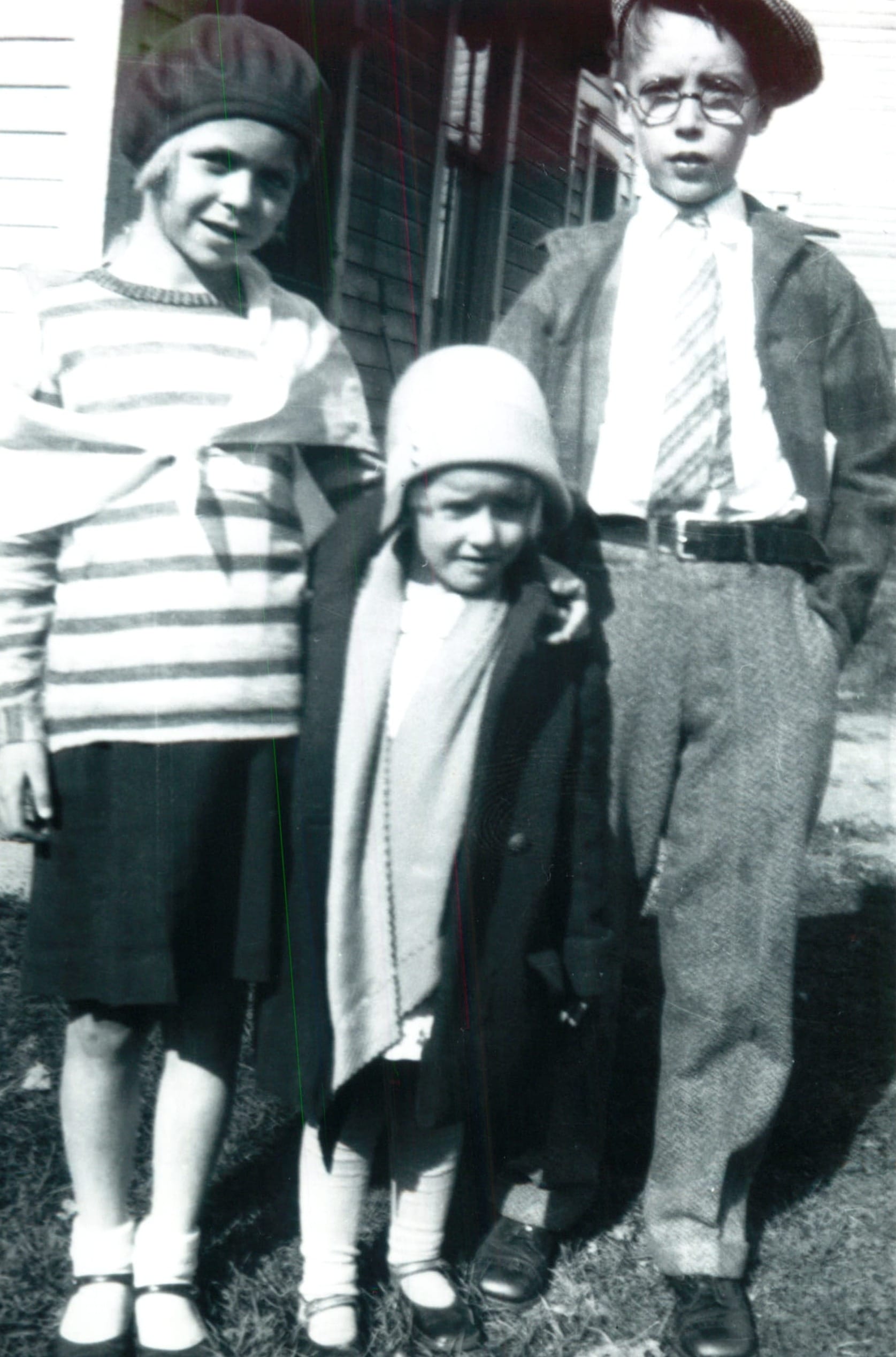

Whatever the forces were that pushed the two of them together in Duluth, Peggy ended up having 3 kids: Lorraine, Arthur, and Betty.

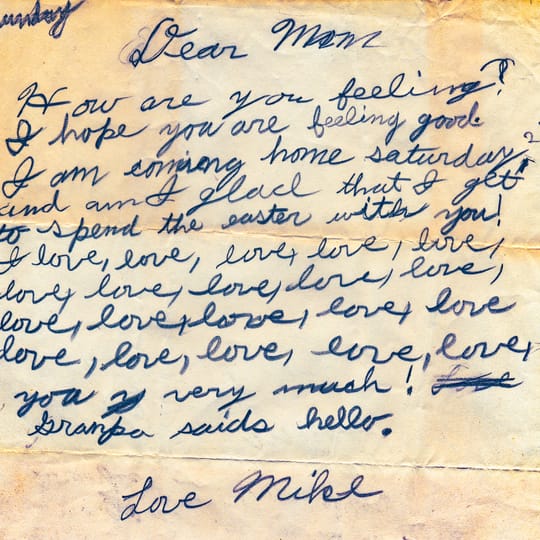

That's all I know about Lorraine in her early years. In Peggy's old trunk is a pile of photos of Lorraine when she was young that paint a picture of her being a rather vibrant and (I could be imagining or want to see her in this way) free spirit. It is also interesting to imagine who is taking the pictures......

Lorraine ended up in Minneapolis, as did Peggy, but I know nothing else about the move from Duluth or any other details except that she ultimately married a man named Howard Maddaus when she was a teenager, and they had a kid named Larry Maddaus.

Lorraine was born on January 2nd, 1920, and Larry was born on August 5th, 1939, so my mother was only 19 years old when Larry was born.

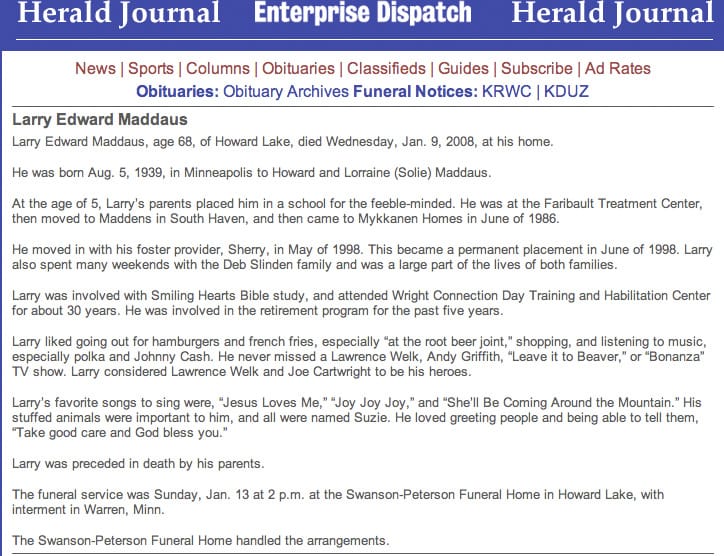

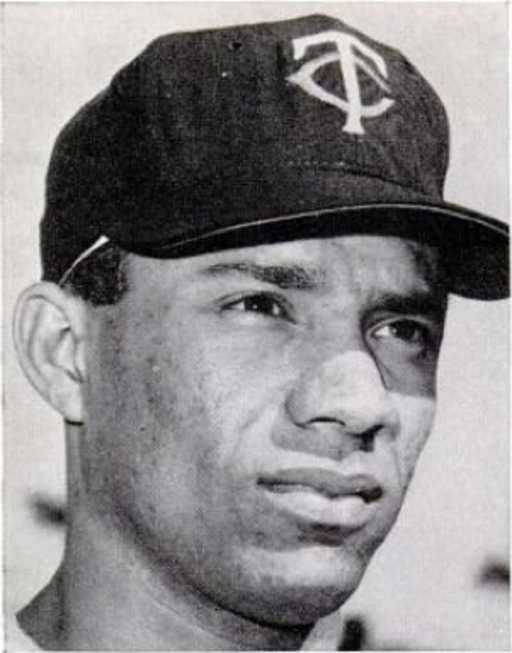

Larry had significant developmental difficulties - you can get a sense of this in the photo above - and he was placed (as his obituary from 2008 below said) in a home for the "feeble-minded." Growing up, I had no knowledge of Larry or of Lorraine having been married before.

This is where one's imagination can help us gain a perspective on another person and their life, and what they are going through or have gone through. It's 1939, right on the eve of WWII, the world is in chaos, uncertainty is in the air, she is a teenager, married, and she now has a child with significant developmental difficulties.

I can picture Lorraine and Howard living in either an apartment or a small home, looking forward to the birth of their child, then perhaps devastated when reality crashed down on them, and the potential strife, conflicts, and challenges it all presented day to day in their lives. It doesn't surprise me that they ended up divorced.

Then, the heartbreak (and perhaps guilt-plagued relief) Lorraine may have felt when committing Larry to a home for the rest of his life. Then she was alone.

The obituary noted that Larry loved the TV shows Leave It to Beaver, one small thing we had in common besides half our genes and the same last name.

I Was Born

Then I came into the world in 1954. During my entire childhood, I was told that my father had died before I was born of throat cancer. It wasn't until I was home on leave from the Navy that my cousin Susan came over and, with glee, as if she had just discovered a hidden treasure, told me what her mother Betty (Lorraine's sister) had just told her - that my real father was alive.

I stormed out of the room, down the hall, into the kitchen, and confronted Lorraine. She fessed up. It was true.

Lorraine had worked at a restaurant in Minneapolis, and she had an affair with the owner, who was married and had three kids. Now I finally understood why on Christmas Eve (after Peggy died and before my future step-father Ralph came along), Lorraine and I would be alone in the dark in our apartment with the Christmas tree all decorated with tinsel and only the Christmas tree lights on, and she would put a hundred-dollar bill on the top of the tree by the angel and start sobing. Every year, she told me the money came from a friend, but it actually came from my real father.

Picture being in Lorraine's shoes in 1954, the year I was born: she's 34 years old, divorced, working as a waitress, very likely lonely, birth control consisted of the withdrawal method (love that clinical phrase to describe that magical moment of life changing decision making), condoms, and the diaphragm which was too expensive and required seeing an MD, which most women could not afford or were embarrassed to do.

I've wondered many times whether Lorraine intentionally decided to have another child, given the march of time and the biological window closing for having another kid, or if it was an accident, or perhaps something in between, like Roulette and seeing if the ball lands on a winning number?

Regardless, there she is in 1954, single, with an illegitimate kid born out of wedlock (we were called bastards back then) from an affair with a married man with three kids. Plus, I can state with near certainty that she must have been terrified at the possibility of having another kid with developmental challenges.

Back to Brene Brown: "Shame loves secrecy. The most dangerous thing to do after a shaming experience is to hide or bury our story. When we bury our story, the shame metastasizes."

I don't think Lorraine had any choice (given the era's social norms) but to "bury our story," the "our" being our story, hers and mine intertwined. So it was until that fateful day when my cousin Susan came over and dumped the truth on me.

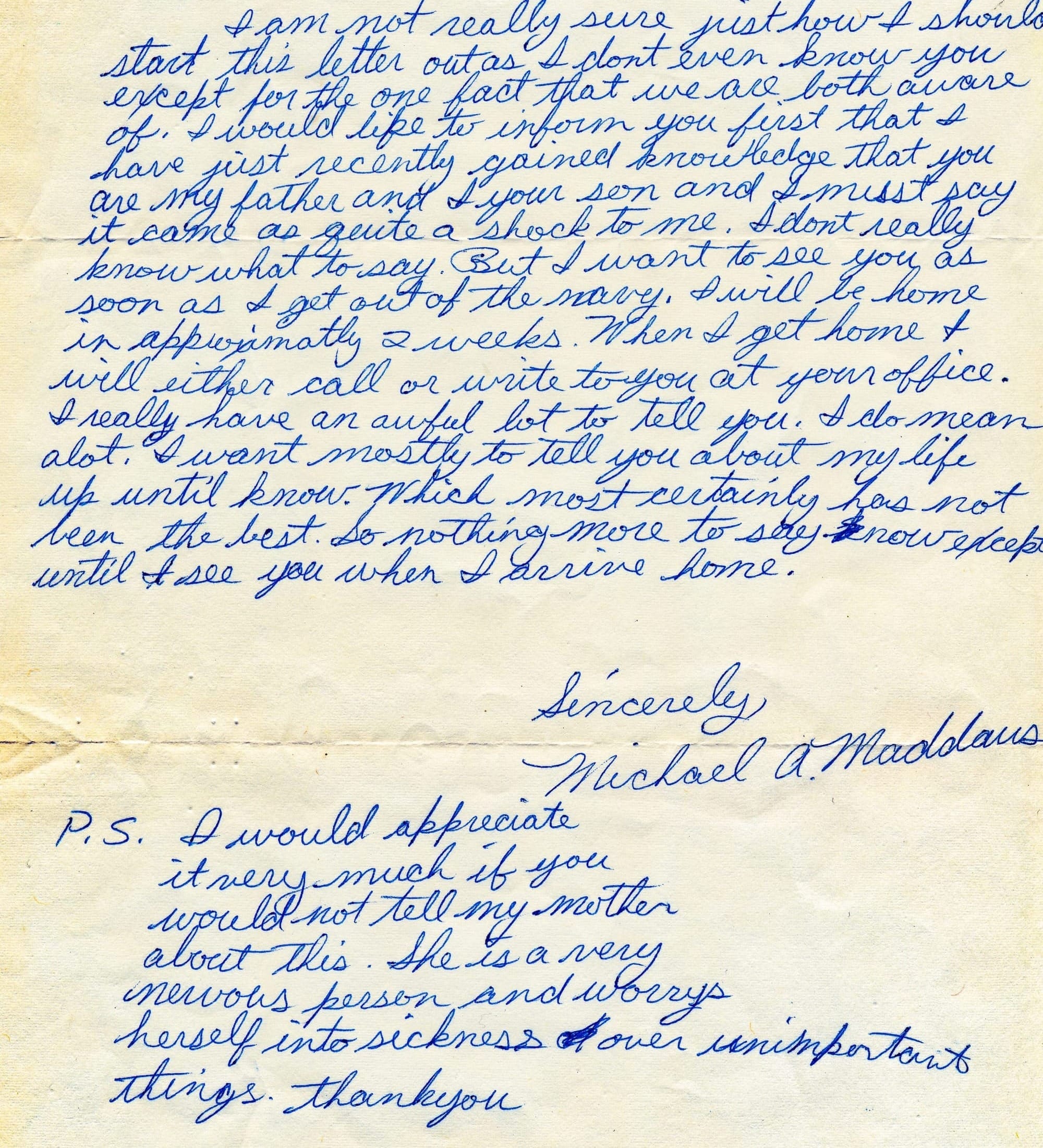

Turns out my real father was still alive. Lorraine tried hard to protect him, and she pleaded with me not to contact him, but I was having none of it. Here is the letter I wrote to him before my Navy leave ended:

I was so excited to meet my real father. What I remember without question is that my only agenda was to have a father, my real one, to meet him and get to know him. I didn't give a damn about him being married or his three kids or money. I was elated to meet him only because he was my father.

After I was discharged from the Navy, I set up a meeting with him in downtown Minneapolis at a restaurant. Walking in, I felt like an excited dog about to get a treat, with my mental tail wagging away with excitement over meeting my real father.

I spotted him, walked over, he stood up and shook my hand, and I sat down in the booth with my tail wagging away. I was in such a trance of me that I assumed he would be feeling the same way!

Imagine his situation: here is a man with a successful business, married with three older children, and out of the blue, this kid who says he is his kid shows up - a kid of a woman he had an affair with over 20 years ago - claiming he is his father. He had no idea what might be up my mental sleeve.

My tail stopped wagging when he said, with his eyes looking down at the coffee cup in front of him on the shiny Formica booth surface, "I'm not sure I am your father - I think your mother had been seeing other men."

I felt as if I was being manipulated into a state of doubt that was likely very intentional. I could feel it. Part of my sense of certainty about his paternity was born of the photos of him that are in Peggy's trunk: pictures of him in the military, and the most telling - a picture of me as a baby propped up on the striped couch we had for over 20 years - he's sitting on a chair in front of me, bent over, his face in front of mine, looking at me with a warm smile and, like a little monkey holding onto a branch, my baby fingers are wrapped around his pointer finger.

After telling me that he had an insurance policy in my mother's name for $3,000 and that he had an old car that he could give me, I realized he was offering me hush money.

I left the meeting with my tail between my legs. But I also left determined not to let anyone make me put my tail between my legs ever again. I never talked to him again. Like so much of my life, I pushed these events off my mental cliff and into the deeper waters of my mind, and drove off down the winding road into my future.

My Young Years With Lorraine

The first memory I have of Lorraine is roller skating in the basement of the duplex we lived in when I was about 5 or 6 years old. We had a pair of roller skates - the kind you put on the bottom of your shoes and strap around the shoes to stay on - and we'd go down to the dark basement, turn on the light bulb hanging from the ceiling, and we would skate around the big furnace in circles with Lorraine chasing after me. I loved it.

That's about it on the memory front until I was 8 or 9 years old.

Lorraine worked as a waitress in downtown Minneapolis (she took the bus to work in the morning and home again at night) in several different restaurants, and her friends were all fellow waitresses who regularly came over to our apartment for highballs. For those unfamiliar, a highball is usually whisky or vodka mixed with 7-Up.

One of the fondest memories I have as a kid is when Lorraine and I would take the bus on the weekend to downtown Minneapolis to The Nankin, a vast Chinese restaurant with a beautiful Art Deco interior.

I LOVED going there. I always sat at the bar drinking Shirley Temples (7-Up, grenadine syrup, and maraschino cherries), gabbing with the bartender, and eating one maraschino cherry after another (an endless supply afforded me by my charming the bartender) while Lorraine sat at a table with her waitress friends drinking highballs.

At some point, Peggy moved in with us (she may have lived with us the whole time - I just don't remember), and she took care of me during the day when Lorraine was working her two waitress jobs, one daytime job and the other at night.

Peggy, being a Norwegian who came over alone on a ship across the Atlantic, was a very stoic woman who literally never seemed to talk with two exceptions: to tell me what to do, and when she put me to bed at night when she would say goodnight and sweetdreams in Norwegian (god natt and søte drømmer) through the crack in the almost closed door to my bedroom. Those nighttime words of Peggy's are the fondest memories I have as a young boy.

It seemed to me that Peggy's days were spent almost entirely at the kitchen table, playing solitaire. Peggy provided structure and a rhythm to my life. When I came home from school, she was always waiting for me at the kitchen table, playing solitaire. She cooked my dinner and made sure I was home to eat, that I did my school work, and got to bed on time.

Then one day, when I was nine years old, Peggy started acting funny. She didn't recognize me, and she wandered around the apartment as if she didn't know where she was. She would become furious over seeing or hearing things that weren't there. Turns out she had been having vaginal bleeding for over a year (never told anyone about it) from cervical cancer that had metastasized to her brain.

Peggy went to the hospital and never came home again. She is buried in a large cemetery in Minneapolis without even a simple gravestone, most likely because Lorraine couldn't afford to buy one.

So now Lorraine had lost her child support, her mother, and the way of life she had fallen into.

Life changed in an instant. Now I was alone every day after school and all evening. My dinners became Swanson TV dinners, Mac and Cheese, frozen hashbrowns, and bacon. Honestly, I loved being able to cook this stuff on my own and watch whatever the hell I wanted on TV for as long as I wanted. But soon the thrill was gone, and loneliness set in as the default state of affairs.

During this time, a Cuban family moved into the apartment across the hall. The contrast of their world with mine was an awakening. Our world was small, stoic, isolated, and lonely. Theirs was gregarious, vibrant, and boisterous. I fell in love with them and pretty much forced my way into their lives. They left their front door wide open most of the time, and you could hear the cacophony of the thick clots of Spanish-speaking people coming and going at all hours.

The mother of the clan took a liking to me and let me help her in the kitchen. To this day, I can remember her showing me how to fry bananas!! No one fried bananas in my world, nor did we eat at a huge table with 10 other people passing mounds of black beans and rice around, all the while talking nonstop and wiping their mouths on the edge of the tablecloth! I loved it.

I even met the famous Minnesota Twins shortstop Zolio Versalles when he came over for dinner one night.

I can imagine how much she may have worried about me while she was at work. There I am, 10 years old, alone most of the time, and I was (as a friend told me when I was in Hazelden), even then, a force to be reckoned with.

A small example of what Lorraine had to deal with. Being 10, bored, and alone after school in our apartment, I decided one day to play a practical joke on my mother. She had an old Singer sewing machine, and she liked to sew, so she had a lot of threads in different colors. I took multiple spools of thread and wove the threads back and forth across the entire living room and in front of the door to our apartment, securing the back and forth thread weavings to the furniture, lamps, and door knobs. It was all set up so that when Lorraine came home and tried to open the door.....Caboom! Things fell all over the place, and there was nowhere to walk. She was not happy.

After Peggy died, men started to come and go in our lives, around for a while, then one day gone. These men were both bright spots in my life (it was so great to have a man around with a car, which gave hope to my dream of having a father) and dark spots - like the anger, crying, and the sounds of Lorraine being hurt from her bedroom at night when one of them (Jack) slept over. My emotions were like a roller coaster, going from the highs of the possibility of a father, followed by the sudden descent to loneliness and betrayal when they simply disappeared.

I can imagine that it must have been so difficult for Lorraine to bring these men home. She had to deal with her loneliness, her desire for companionship and stability (both for me and likely financial), and with how I would react to them. It seems like a pressure cooker to me.

A Father, Finally

Then, when I was around 12 years old, Ralph, my future stepfather, showed up. I presume Lorraine met Ralph at a restaurant where she worked as a waitress or perhaps at a bar.

I remember the first time I saw him as if it were yesterday. He had just been discharged from the Navy after 20 years as a cook.

He had come in the back door of our apartment and was standing in the kitchen in his Navy uniform, cigarette in hand, all smiles. I was smitten. Perhaps my father had finally arrived.

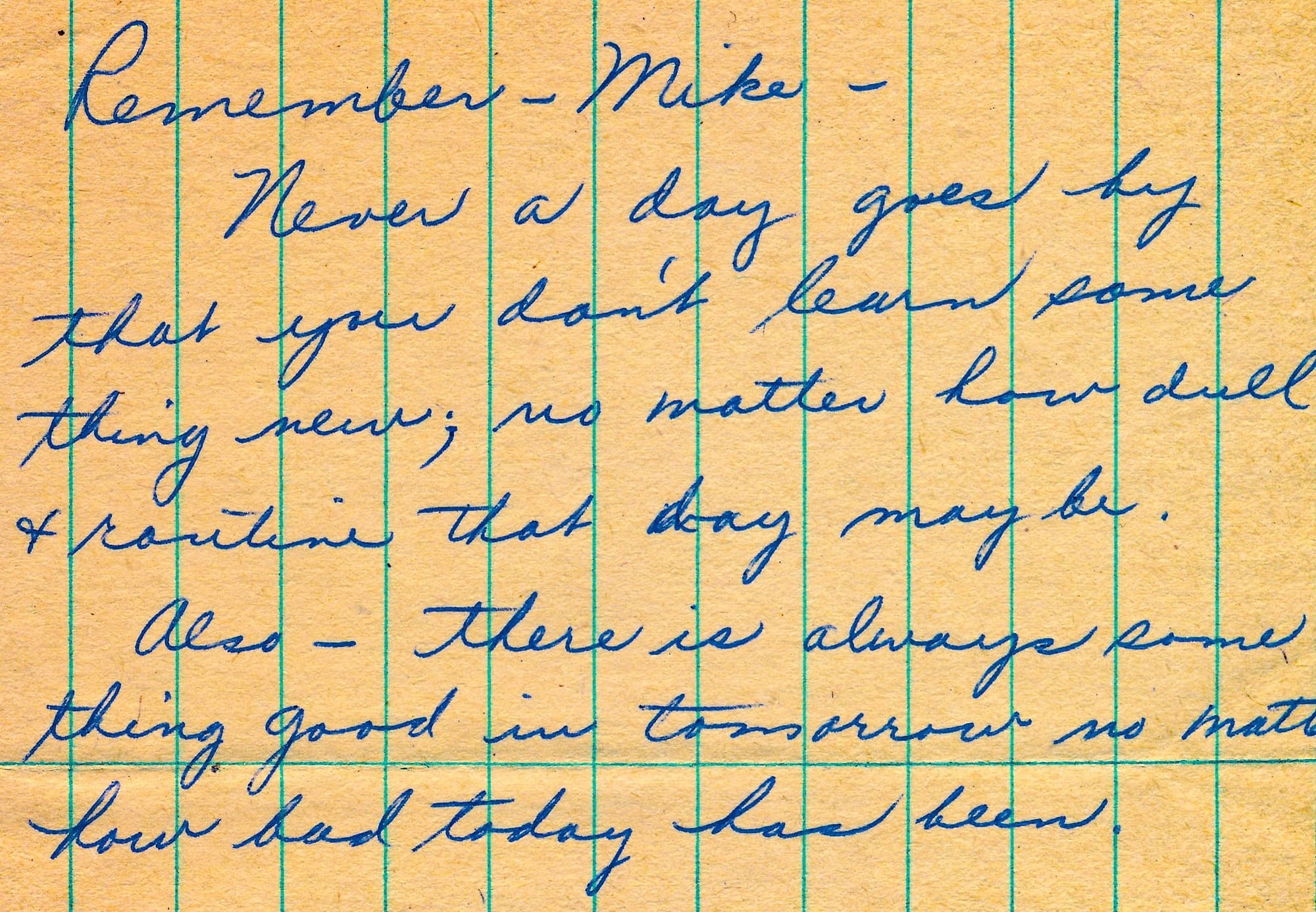

It was all roses in the beginning. He started working full-time at night as a guard at a factory. He was nice to me, and Lorraine was happy and was able to quit her nighttime job. Now she was home and cooking dinner, and we ate as a "family." My mother bought me a diary that I found stashed away in Peggy's trunk several years ago.

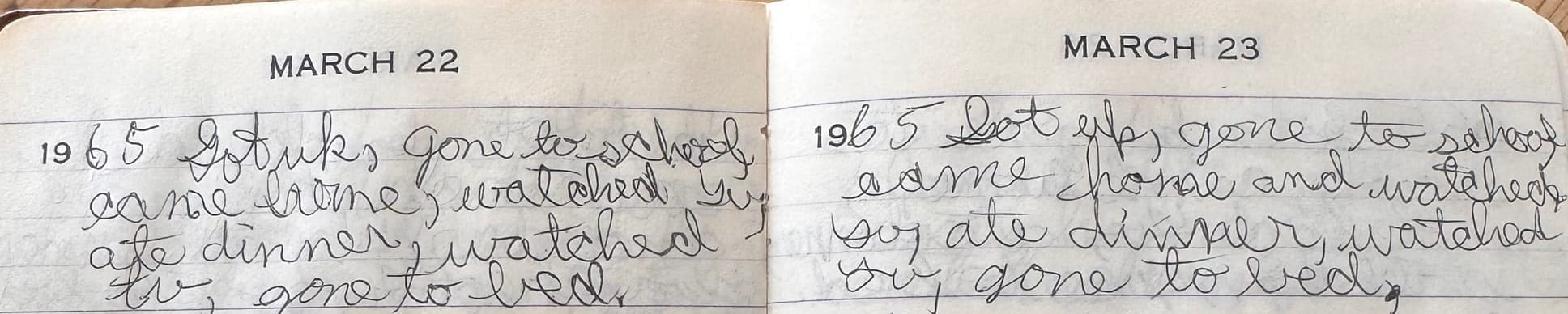

Here is an entry that repeats itself at least 50 times on page after page, with the smallest variations: "Got up, gone to school, came home, watched TV, ate dinner, watched TV, gone to bed."

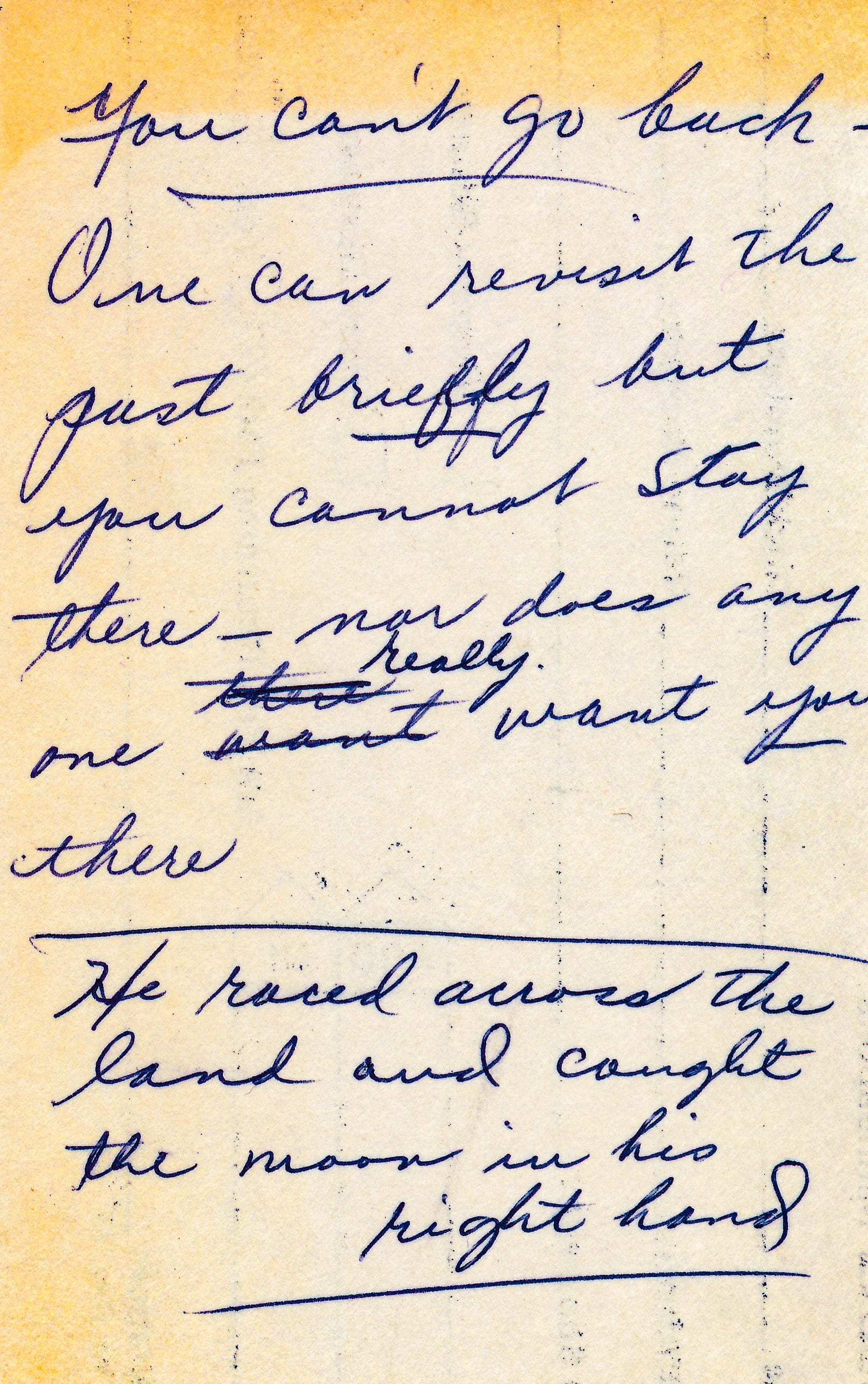

Then things slowly started to change. Lorraine was a smart lady, and she cared about manners and liked to read and cook. She had several cookbooks that she made dinners from that are still in Peggy's trunk, and she was always writing notes on small bits of paper like these.

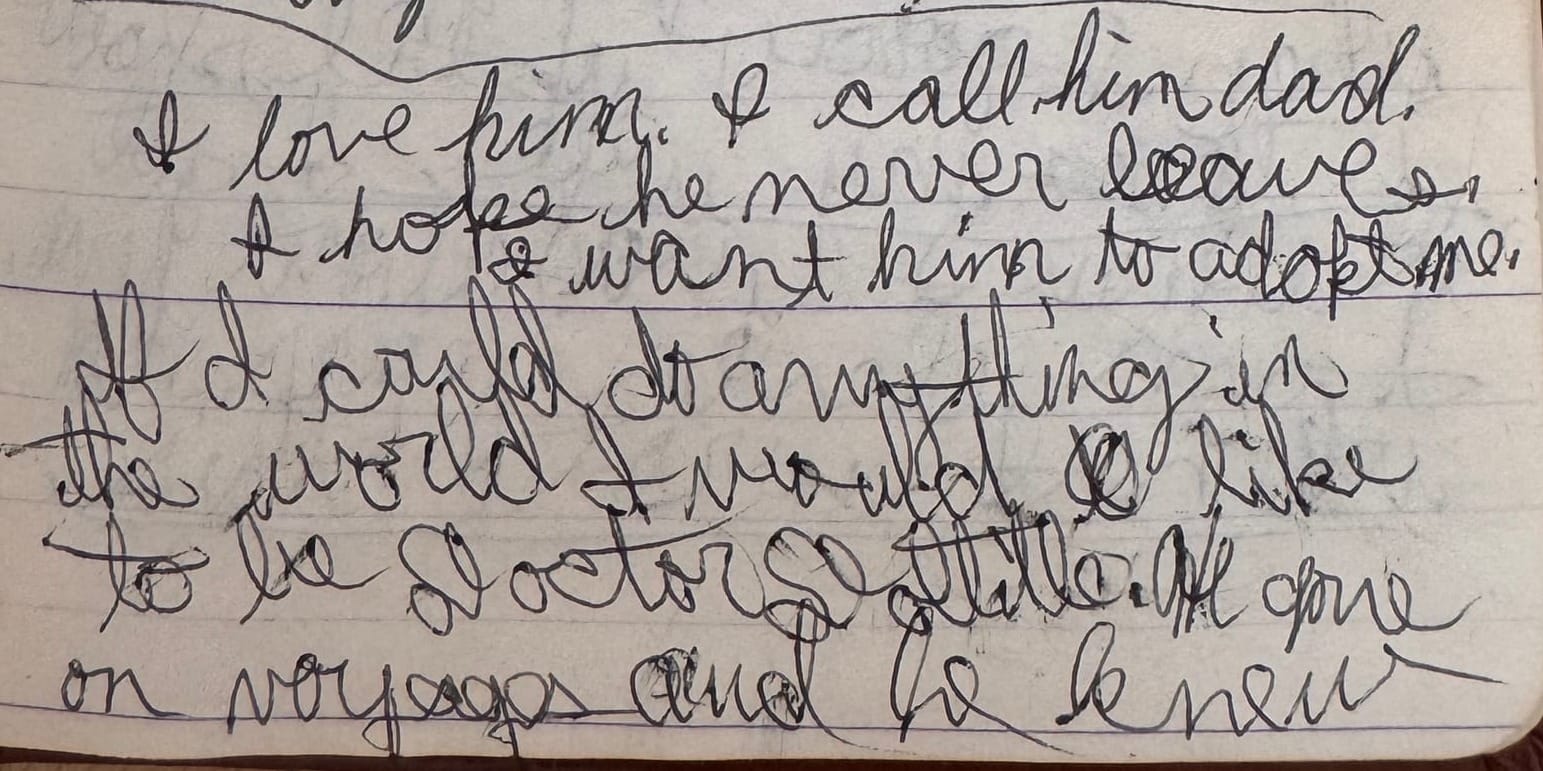

The image below is of an earlier entry in my diary about loving Ralph and wanting him to be my dad, along with professing my love of Dr. Dolittle, who could talk to and understand animals. It says: "I love him. I call him dad. I hope he never leaves. I want him to adopt me."

Ralph was not too bright (I am being kind here), and his communication was crude and rough (and meaner and meaner as time went on).

He relentlessly bitched about money, and I soon became the target of his financial anxieties. I was young and growing, and like most young boys, hungry all the time, and I was always going to the fridge to find something to eat.

Ralph was usually parked at the Formica kitchen table in the mornings, drinking coffee after coming home from his job as a nighttime guard, and at night drinking highballs before going off to work in his grey guard shirt with his gold badge and his black metal lunch bucket in hand.

When he was at the table he was the fridge guard dog: whenever I approached the fridge to look inside for something to eat (the damn thing was pretty baren - but I've always been very optimistic) he would look at me with seething contempt - and with dark slit like eyes that say "I hate you," and then bark "you're eating out of house and fucking home."

This caused no end of conflicts between Lorraine and Ralph as she played the role of protector and he the troublemaker. Another area of relentless tension was the dinner table, where Ralph would put his forearm across the table in front of his plate and park his face directly over the food like a helicopter hovering above the landing pad, and shovel the food in with the other hand, one load after another. It drove Lorraine nuts, and her irritation soon became mine.

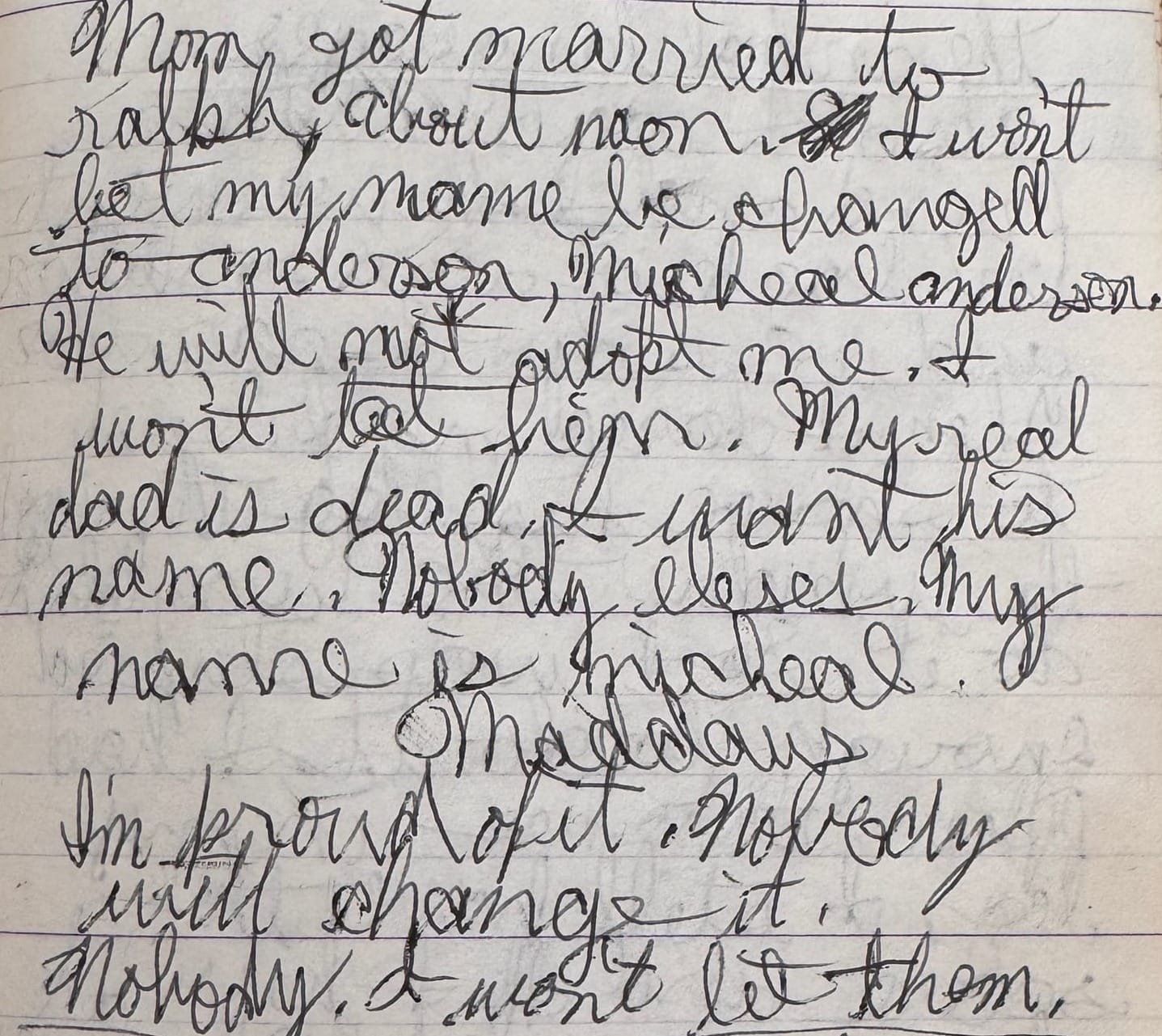

Over time, I grew to hate him. Here is a later entry in my diary after they were married: "Mom got married to Ralph about noon. I won't let my name be changed to Anderson, Micheal Anderson. He will not adopt me. I won't let him. My real dad is dead. I want his name. Nobody elses. My name is Micheal Maddaus. I'm proud of it. Nobody will change it. Nobody. I won't let them."

I can imagine the tension, struggle, and guilt she may have felt. She was trying to manage Ralph and their relationship, and me and our relationship. It was a triangulation setup from hell.

Not long after they were married, Lorraine quit her last job as a waitress and became a "stay-at-home mom."

Life Changed in an Instant, Again

I loved (seriously, I loved) building plastic models, especially of the monsters in the horror movies of the day like The Creature from the Black Lagoon, The Wolfman, and Count Dracula. I've always been very organized and detail-oriented, so I loved setting up all the plastic pieces on one side of the table, putting the paints and glue on the other side, and building my monsters. My finished products were proudly on display on shelves in the dining room.

I suspect many of you can recall a defining moment when you were a kid and you suddenly woke up to the reality of life and your parents. It is like the bubble of childhood innocence bursts, catapulting you into the real world of adults. I had two such moments. The first time was when I was about 5 years old, when Lorraine told me that we all die, and the other time was on a Sunday morning when I was 11 years old.

I always get up very early, and when I was a kid, I woke up spontaneously around 6 or 7 at the latest, way before Ralph and Lorraine on the weekends. On this particular Sunday morning, I'm up early as usual, and I've set up shop in the dining room with my cardboard table and my Frankenstein model.

A few hours later, Ralph and Lorraine wake up and saunter by me sitting at the cardboard table with my boy Frankenstein on their way into the kitchen.

Meanwhile, I'm so deep into working on my Frankenstein model that I'm oblivious to time and what they're doing in the kitchen, so I didn't notice when Lorraine eventually comes into the dining room until she was at the record player over in the corner.

I look up and see her standing at the record player in her white terry cloth robe with a wad of Kleenexes stuffed into one pocket, struggling to put a record on. After fumbling around for a minute, she manages to get the song El Paso by the country western singer Marty Robbins going:

"Out in the West Texas town of El Paso

I fell in love with a Mexican girl

Nighttime would find me in Rosa's Cantina

Music would play and Feleena would whirl

Blacker than night were the eyes of Feleena

Wicked and evil while casting her spell

My love was deep for this Mexican maiden

I was in love, but in vain, I could tell"

Lorraine turns around, faces me, then stumbles over to me with the front of her white robe open, her small breasts showing (fried eggs Ralph once called them in front of me), with only her panties on, and with her arms stretched out in front of her like Frankenstein (I know, the irony) came to the side of the cardboard table and asked me to dance with her.

Turns out they were drinking highballs that Sunday morning. It was one of those traumatic moments where one can recall every detail of the scene - her drooping eyelids, the robe, the Kleenex, the smoke in the room bellowing out from the kitchen, her panties, her fried egg breasts, all of it burned into the grooves of my mental hardrive for as long as I will live. I didn't take her up on her offer to dance. Instead, I ran to my room, and that's the last thing I remember.

That Sunday morning opened a Pandora's box of misery and a pattern of living that would haunt all of us for the next 12 years until she finally died when I was 25 years old.

The pattern was this: Lorraine would drink whiskey and 7-Up highballs, slowly stop eating and lose weight, and with the weight loss, her gums shrank so her dentures no longer fit, so she would eat even less. Eventually, she would become so weak that she ended up bedridden, with Ralph and me bringing in food or water or highballs (Ralph took care of the highballs).

I remember sitting in the chair by her bed, in the dark room with shades drawn and only her bedside light on, the ashtray on the bedside stand filled with cigarette buts, day after day, pleading with her to eat.

Then, when she was soiling the bed and near death, Ralph and I would get her dressed, help her down the back stairs and into the car, and off we drove to the hospital so she could dry out. Ralph would take me to visit her once or twice, and seeing her getting better and talking normally again would fill me with hope that it would not happen again.

After a couple of weeks, my "real Mom" came home. For 2-4 months, she cooked dinner, we ate as a family, and her real, warm, and caring personality blossomed like a flower.

But the day always came when, as I walked up the stairs to our apartment after school, I could feel it in the air that she was drinking again. I could actually feel it in my gut as I put my hand on the door knob of our apartment, and when I opened the door the slight slur in her voice was like a bolt of lightening that would bring me to my emotional knees.

Rinse and repeat, over and over, until she finally died in 1977 when I was 23 years old. My world swung from despair and hatred of her and Ralph to hope and even joy when she came home from the hospital, praying she wouldn't do it again. But she did do it, again and again.

For those of you familiar with vinyl record players, if a part of a vinyl record gets played enough and worn down, the needle can get stuck in a grove and play the same part of the song over and over until you get your butt up out of the chair and lift the needle up and set it back down in another spot on the record.

The brain can be like a vinyl record, too. When something is repeated or played enough times, the needle of your mind can get stuck in the well worn groove of an experience that can haunt you, until you get your mental butt up out of a chair to move it past the problem groove.

It may have been different if Lorraine had been drunk all the time, since at least then there would have been no hope of change.

But, vascillating between the dark hell of living in an Ingmar Bergman-like movie when she was drinking and how wonderful and loving she was when she was sober kept my mental needle in this groove in my brain:

"Why does she keep doing this to me?" is the refrain that played in my mind for all those years, followed by "I hate her." Over the years, the volume of the refrain diminished, but it never went away, totally, until I ended up in Hazelden.

It felt personal, because it was personal, to me.

Of course, Ralph had it figured out why she was doing it to me - she kept relapsing because of me getting into trouble and all the anxiety she had about me. Never mind that the drinking started well before the day I was working on my Frankenstein model, and well before my first arrest (of 24) for shoplifting.

The combination of Lorraine "abandoning me" over and over with Ralph's blaming me for Lorraine's struggles and for a big chunk of their financial woes fostered a deep hatred of my mother and Ralph. It was black and white for me. She didn't really care about me. If she did care, really care, she would not have done it to me, again and again.

The bookend of this whole saga came about in 1977 when I was 23 years old. I was out of the Navy, I had my GED, I was a student at the University of Minnesota, I had a girlfriend, and I was really doing well.

Lorraine had been "dry" for a while. I went to see her one evening, and once again, as I was walking up to her front door, the feeling was there, in my gut, again. I could feel something in the air, like one feels just before a storm - the sudden pressure shift and temperature change. I knocked, heard her say "come in," and I could tell from her voice that she had been drinking again. I walked in, and sure enough, despite her trying to pretend, she was drunk.

I turned around and walked out, seething with hatred, but also free, at last. I was done. Ralph and Lorraine could no longer blame me for their problems. That was the last time I saw Lorraine alive.

Not long after, she died from cirrhosis at the county hospital. I went to the funeral, walked in, looked at her pickled body in the casket, and walked out before the service, refusing to talk to Ralph, my aunt Betty, or my cousins.

I was finally free of her and everyone associated with her, for good, or so I thought.

Life Went On

I was done with that part of my life, and I never looked back. I pounded like hell, got into medical school, then surgical residency, and I had a great and successful academic career.

Then, 35 years after her death, I end up in Hazelden for prescription narcotic addiction. This is where things get darkly humorous. There I am in rehab, but NOT for alcoholism. Not me. I hated alcoholics. Seriously, I hated them. I was different because I was addicted to narcotics.

Of course, I had my face rubbed in my own mental excrement when, after getting out of the 24-hour detox unit, an alcoholic was assigned to give me a tour of the place. Not just an alcoholic, but a medical student, and a medical student from of all places, Harvard, a place where John Najarian (the famous chair of the Department of Surgery at the University of Minnesota) said that people don't think their shit stinks.

Well people from Harvard may not think their shit stinks, but my attitude toward the whole rehab affair did stink, and everyone could smell it since, as many of you know from previous posts, that I was (seriously) voted least likely to succeed by my fellow inmates.

So I looked down (in my mind) on my "fellow" alcoholic inmates with contempt and derision - and I avoided them as much as possible, as I preferred to be around the young heroin addicts in my midst.

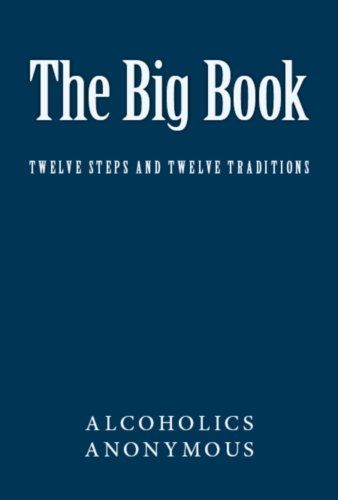

Now, Hazelden (when I was there in 2012) was essentially a reeducation camp that steers lost souls into the catacombs of the Alcoholics Anonymous 12-step program. Part of the protocol is learning to refer to yourself as an "addict," and the other part of the reprogramming is to read the "Big Book."

The Big Book. My counselor strongly encouraged me to read the Big Book. Not being an alcoholic, I refused. The blue cover with the embossed words Alcoholics Anonymous triggered disgust, and early on, my days were spent walking around the rehab prison in a thick mist of resentment toward all of the alcoholics in my midst.

The crack that let a bit of light into my ossified perspective came during one of our daily group sessions. The counselor read a story about an alcoholic, sober for 25 years, who retires from work and thinks that he has earned the right to drink like other men. So he puts on the carpet slippers, grabs the bottle, and two months later ends up in the hospital. The dark humor of his slipping up while wearing his carpet slippers and slipping down the steep slope of justifications made me curious to read more.

That night, while the rest of my fellow inmates were watching TV in the commons, when I was in my room alone and safely out of view, I sat down on my bed cross-legged and cracked open the Big Book and started reading some of the stories. And honestly, I found so many of them warm, compassionate, interesting, relatable, and often darkly humorous.

Then I came across a story about a daughter's forgiveness of her father for all of his miserable behavior when he was drunk. As I was reading, a sudden tectonic shift came over me, a second-order change. In an instant, the handcuffs of resentment and anger toward my mother came off, and I saw my mother for what she really was: a human being, a woman, struggling like all of us, who did her best to play the game of life with the shitty deck of cards dealt to her existence.

I found myself sitting on the bed with the Big Book, sobbing. Years of sewage finally poured out.

For the first time, the tsunami of her life washed over me. Instead of seeing her in black and white, as this thing or person who did these miserable things to me, I was able to behold her as a human being.

To behold someone is a state of complete acceptance and even embracing someone for who they are, without judgment and free of the trance of me and seeing everything through the foggy perspective of my mental lens.

I came across the concept of Beholding someone from the incredible book by David Brooks called How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen. Here is a passage from the book about him Beholding his wife (italics and bold mine):

"One day, not long ago, I was reading a dull book at my dining room table when I looked up and saw my wife framed in the front doorway of our house. The door was open. The late afternoon light was streaming in around her. Her mind was elsewhere, but her gaze was resting on a white orchid that we kept in a pot on a table by the door.

I paused, and looked at her with a special attention, and had a strange and wonderful awareness ripple across my mind: “I know her,” I thought. “I really know her, through and through.”

If you had asked what it was exactly that I knew about her in that moment, I would have had trouble answering. It wasn’t any collection of facts about her, or her life story, or even something expressible in the words I’d use to describe her to a stranger. It was the whole flowing of her being—the incandescence of her smile, the undercurrent of her insecurities, the rare flashes of fierceness, the vibrancy of her spirit. It was the lifts and harmonies of her music.

I wasn’t seeing pieces of her or having specific memories. What I saw, or felt I saw, was the wholeness of her. How her consciousness creates her reality. It might even be accurate to say that for a magical moment I wasn’t seeing her, I was seeing out from her. Perhaps to really know another person, you have to have a glimmer of how they experience the world."

All I can add to Brook's beautiful experience of his wife is my belief that, if you want to, you can learn to behold others as a skill, even if you have not lived with them for 30 years. Just pause, look, and with your mind's eye and imagination get curious about them and about the chain of fortuitous concatenations and forces that led them to where they are at that moment.

Root Cause Analysis of Lorraine's Alcoholism

At this moment, as I am sitting here writing these words, it hit me that one way to open the door of understanding another person is to do a Root Cause Analysis of them. Bear with me for a minute here.

Although Root Cause Analyses are associated with incidents with negative outcomes, it need not be confined to being a method for untangling a failure or bad outcome. It can also serve as an excellent frame for trying to understand another human being and how they became who they are, and why they are doing what they're doing at a given time in their lives.

In this revised paradigm, a Root Cause Analysis would carry neither negative nor positive connotations. It becomes a way of thinking about how to get to know, or even behold, another person.

I even renamed it to Root Human Analysis.

In other words:

Root Human Analysis = The process of discovering the Fortuitous Concatenations of a person's life that lead each and every one of us to be who we are at a given moment in time: that accretion of the complex amalgamation of genetics, personality, and parental, social, and career forces that drive all of us to today, to the present moment.

I wish so much and with all of my heart that I could talk to my mother, Lorraine, so I could hear about her life and its highs and lows, so I could really see and behold her with depth.

I genuinely have no regrets about my life in general. I have made a mess of some things for sure, but I have learned and grown from everything I have been through and it has all gone into the Michael Maddaus Fortuitous Concatentation recipe which produced the Michael Maddaus sitting at his computer typing these words while in Ushuaia, Argentina (more on that later!).

But I do have one regret: that I did not understand these things when I was younger, when the opportunity to really learn about my mother's life was available to me. I miss my mother, and I regret having missed the opportunity while she was alive. I also regret it because I can imagine how great it might have felt for her to talk with an open heart and vulnerability about her life and struggles.

If she were here with me at this moment, I would look her in the eyes, wrap my arms around her, hug her tightly, and say:

"Mom, I love you so much, and I am sorry for how life must have been so hard for you, and I am also sorry for all the misery and anxiety I must have caused you when I was such a troublemaker. I can imagine how hard it must have been for you to see me struggle so much, and I hope you can forgive me for all the problems I caused in your life. And mom, I want you to know that I was so mad and angry with you for years for the drinking and the misery it caused, but that I forgive you, in my heart, without reservation, and I wish so much that I had had the skills and understanding to help you, for you must have felt so alone in the world.

I also want you to know, without any doubt, that who I am today is because of you - all of it, the good, the bad, and the ugly - and for that reason, I am so grateful that you are my mother.

I love you, Mom."

Feedback with a thumbs up or down is greatly appreciated, or drop an email to me michael@michaelmaddaus.com.