Spotting Our Blind Spots - The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly

On June 12th, 2012, I was released from my incarceration at Hazelden rehab center in Center City, Minnesota, after being convicted as an addict and sent there for the 3-month physician program.

Walking in the front door was, well, weird and very awkward. I suspect that my transition back home, and my wife and children's transition to having me back, was much like that of a soldier returning from deployment. They adjusted and learned how to live in my absence, and I had been through the hellish experience of rehab and had endured an all-out attempt by the organization to brainwash me into the world of the 12-step AA program.

I tried to embrace the 12-step protocol, but there was almost (none really) science to it, and it required a relentless assessment of my character defects and asking God to remove them.

I was more of the mindset that it was my work to remove them and not God's. But where to begin?

One day, with my daughters Maya and Anne at school and my wife, Lea, at work, I was sitting at my desk pondering just how I could have "allowed" myself to become addicted to prescription narcotics. Following the scripted surgical personality routine burned into me, I took full responsibility for the miserable event, but I was still simply unable to understand how I could have lost such control over a bottle of tiny white pills that slowly came to utterly control my entire world and ruin it.

As I mulled all of this, I suddenly recalled a 360-degree evaluation I had done as part of a leadership program I had created for the residents at the University of Minnesota. It was in a file folder tucked away deep inside a drawer full of old papers.

I dug it out, sat down at the desk, and reviewed it, but this time with an entirely different lens and perspective. Let's turn directly to the rater's written comments on my "strengths" and then "areas for improvement."

First, the Good (so you don't think I am a complete loser): charming, charismatic, visionary, inspiring, thinks outside the box, dedication, would let him operate on me anytime, no one better at seeing the future, great with patients and families, his interest in improving himself and other seems endless, fiercely loyal, resilient. If I recall correctly, this is the section I focused on exclusively at the time.

Next the Bad: can bulldoze over other's concerns when he is passionate about a project, is not always open to other ideas, could listen more, very strong-willed and can bowl over colleagues, needs to turn the intensity down, can be dictatorial towards dissenting opinions he does not share, blunt mannerisms, needs to slow down.

Now the Ugly (from one resident - I reproduced the entire thing for context): Dr Maddaus is simultaneously harsh and largely unyielding, unless one is in near-total agreement with him. Nevertheless, his overwhelming popularity is a testament to the potency of his personal strengths. Although his strong sense of self makes him courageous in many regards, I think his unshakable self-confidence (and sense of being 'right') often closes him off to other perspectives that are gentler or quieter than his own. In some ways, he seems almost ruthless in his pursuit to make us strong, leaving a trail of somewhat crushed personalities, which I think he believes is good for us. The irony is that most of us would never complain b/c his approval, favor, and attention are so meaningful. Moreover, most residents are desperate for leadership and guidance, so whatever the cost, Dr. Maddaus stands out as a role model of success, and we want his hand on us. One peer put it perfectly; 'He's like an abusive boyfriend who you absolutely adore, but who you can never be sure won't slap you.'

I had a hunch who wrote it, but I blew it off. After all, the other comments were so good, but more importantly, my thinking at the time was that I was getting innovative and valuable stuff done and that there was bound to be some collateral damage.

Now, sitting at my desk, home alone, with my ass having been handed to me, I began to wonder. Could the abusive boyfriend comment be true or have some truth to it? I wanted to know, but I also didn't want to know - cuz it can hurt, right?

Given my situation and my desire to figure myself out (after all, I had been on a juggernaut of action and little to no real reflection for nearly 40 years, and my 3-month incarceration was the first full stop to reflect I had in my life), I decided that I definitely wanted to know if it was true.

So I asked my kids if I could send them something someone had written about me and that I would like their honest opinion about it. To mitigate the pressure, I asked them to be honest and to write their thoughts to me. Here is what they wrote:

"The slap sentence was perfect. Essentially unapproachable."

"Couldn't tell you anything. I knew I would hear "buck up, move past it, this is nothing."

"Yeah, that was your dictator phase."

Sam, a massive, massive introvert, simply wrote: "Yep."

Thankfully, they all drove home the point that they did not hate me and that they had enormous love and respect for me. But still!

OUCH!

This is a Classic Blind-Spot issue. I swear to God, back then I actually viewed myself as easygoing, approachable, and understanding. Hmmmm.

Spotting Our Blind Spots

In their sensational book, Thanks for the Feedback, Douglas Stone and Shiela Heen (Ms. Heen will be a guest on The Resilient Surgeon podcast this fall!) the authors (who also wrote the classic Difficult Conversations) make the point that businesses pour billions of dollars per year into feedback training that fails miserably.

The return on such a large investment? 51% of people feel their performance reviews are unfair or inaccurate, and 25% dread them more than any other aspect of their working lives.

The reality is that receivers of feedback are in control of what they do and don’t let in, how they make sense of what they’re hearing, and whether they choose to change.

Because of this reality, the authors argue that we need to shift from pushing feedback training and performance reviews, which only generate resistance, and move instead to a pull type of force - meaning we need to spend our time and efforts teaching the receivers of feedback to become more skillful learners.

So, instead of obsessing over training people to give feedback, let's obsess over helping all of us to master the skills necessary to:

- Drive our own learning

- Recognize and manage our resistance

- How to engage in feedback conversations with confidence and curiosity

- When the feedback seems wrong, find insight that might help us grow

- How to stand up for who we are and how we see the world, and ask for what we need

- How to learn from feedback—yes, even when it is off base, unfair, poorly delivered, and you’re not in the mood.

This reminds me of the concept of Extreme Ownership from the ex Navy Seal Jocko Willink. Each of us, individually, is the key variable in our personal growth - not anyone else. Of course, others can play a huge role, but it is ultimately our individual responsibility.

As the authors note: “if we’re serious about growth and improvement, we have no choice but to get good at learning from just about anyone.”

That last statement sums up the situation with the abusive boyfriend comment. The resident who wrote it did not fit the "typical" surgical personality. She was not aggressive and hyperactivated. She was kind, thoughtful, smart, and very calm, and she routinely challenged my thinking in many ways.

If I am being candid, part of the reason I did not take her comment seriously is that she did not fit the mold of a typical surgical resident. This is classic: seeing only what you want to see and ignoring the rest. Never mind the other shorter comments that clearly supported her thesis.

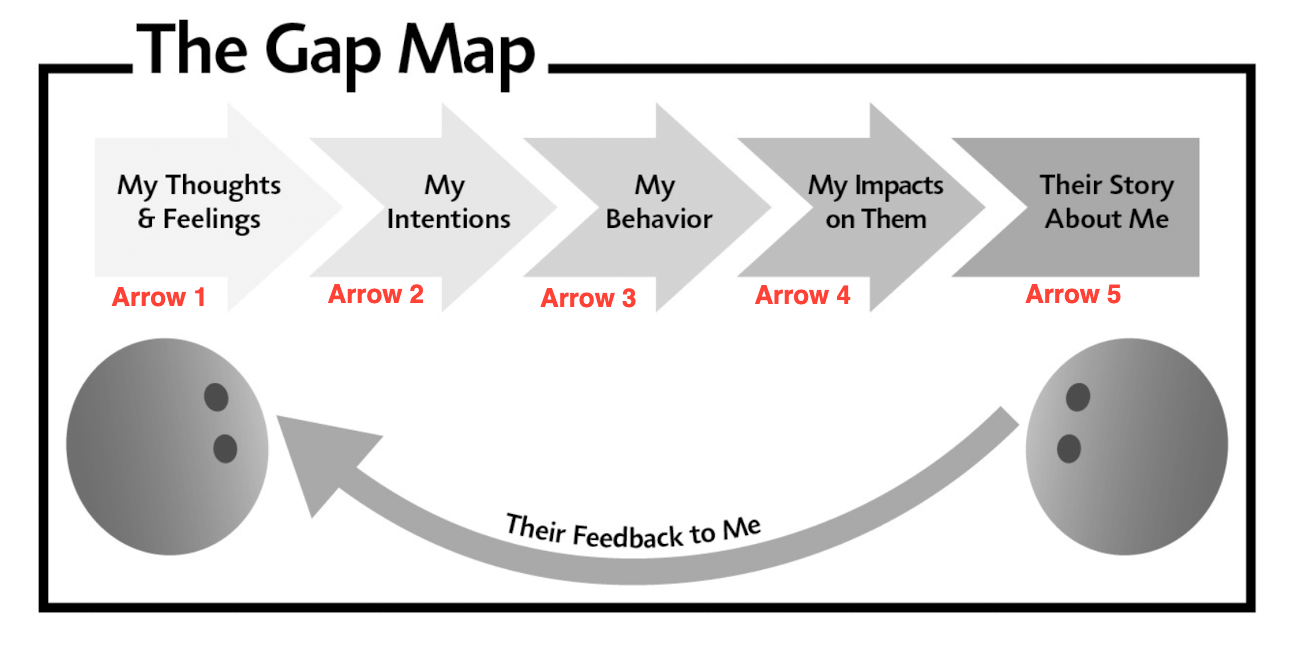

To understand how Blind Spots work, you need to understand the Gap Map.

Moving from left to right: we have thoughts/emotions, and these lead to our intentions - what we are trying to do or to make happen. To get it to happen, we put our behavior out into the world, which impacts others. Then, people who observe our behavior create a story about our intentions and our character. Then we get that feedback.

Here is a great example from the book of the Gap Map and its nuances in action:

- Andrew had a 360 review 3 years ago in which he was told that his subordinates felt he did not treat them respectfully. He was dismayed since he actually wanted to be nice, so he worked on being more respectful.

- Andrew worked on changing his behaviors (arrow 3 in the Gap Map above) but - and here is the thing - his thoughts and feelings remain unchanged. This is a problem.

- What are his thoughts and feelings? Well, they are embedded in expectations and assumptions that have accrued over many years. Andrew has high standards for himself and others - a result of his personality, early family life, and school experiences where he received a lot of positive feedback about his resourcefulness.

- “Like a town that slowly takes shape on the curve of a river, these experiences accumulated into a village of values, assumptions, and expectations about what it means to be “good” or “competent.” So deep down inside, this is where Andrew is coming from.

- Andrew's little river swells up when team members come to him with questions he would have figured out on his own, leading him to believe they aren’t trying or don’t care enough. Result? He often feels impatient, annoyed, and disappointed in his team.

- This creates a MISALIGNMENT between his internal thoughts and feelings on the one hand (arrow 1) and his intentions on the other (arrow 2).

- Andrew thinks he is keeping this misalignment hidden, but those internal thoughts and feelings LEAK INTO HIS BEHAVIOR through his facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language.

- A repeat 360 is done, and the same comments surface from his team members. Andrew sees his intentions as positive—“I want my colleagues to feel respected, and I am trying hard to act respectful.” But his team members see him as deceptive and even manipulative—“You want us to think you respect us when you don’t. Now you’re not just disrespectful; you’re disingenuous.”

- After the second 360, Andrew and his team are in a challenging downward spiral.

It is easy to see how locked in we can become without a deeper understanding of the dynamics below the surface. By understanding these deeper dynamics, we can come to a deeper understanding of each other (getting pretty deep here).

Let's break it down a bit for clarity.

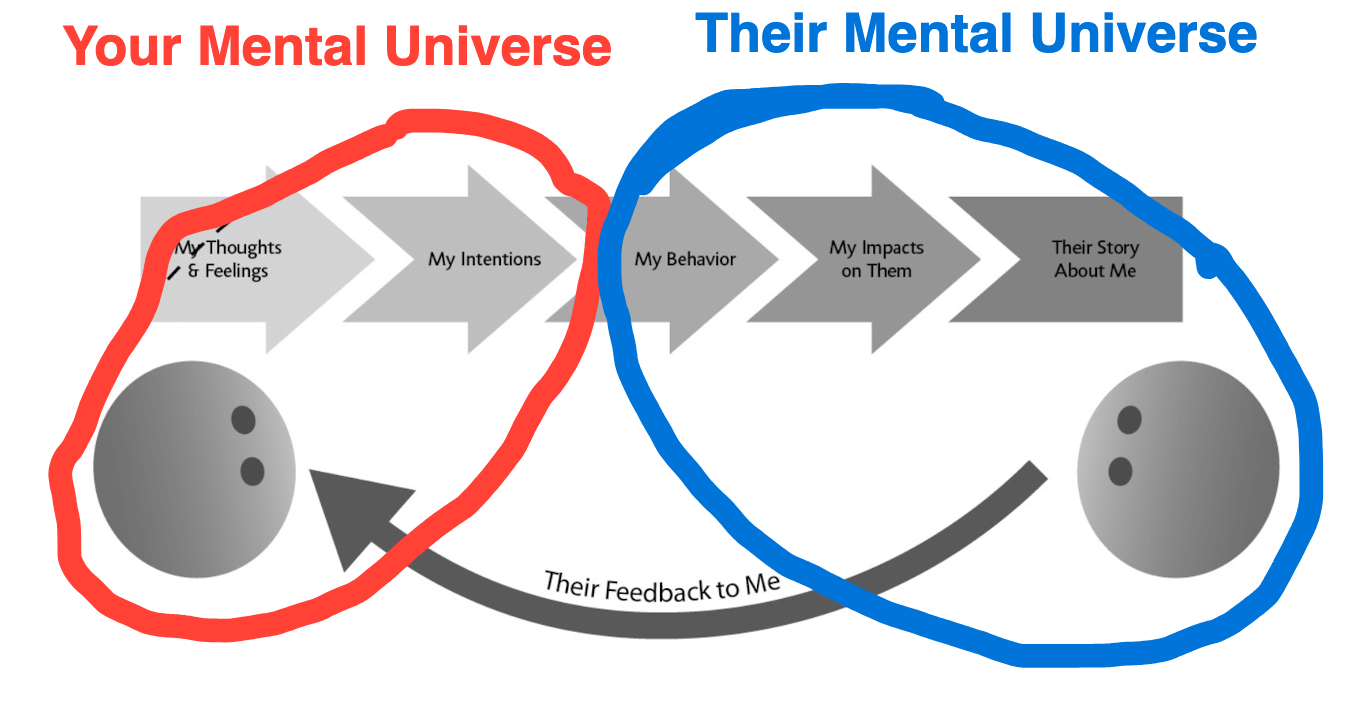

- Each of us is aware of our internal thoughts, feelings, and intentions - our own secret little universe.

- Our behavior is a manifestation of our thoughts, feelings, and intentions, and our behavior is what the other person experiences, as they are not privy to our thoughts, feelings, and intentions. In general, we are all utterly unaware of our behavior and how we come across.

- Since the other person only experiences your behavior, they are forced to make assumptions about what your behavior means, and since assumptions are the mother of all f#@*ups, this is clearly a potential problem. Their assumptions, if not checked with a mindful perspective taking of the other person (a very rare skill, in my opinion), will lead people to create a story about you and your behavior, since we human beings love to have an explanation for everything.

There are 3 reasons we are unaware of our behavior and how we come across to others:

- Our Leaky Faces. We cannot see our faces. Our face is a blind spot. Humans read facial expressions like a Geiger counter picks up radiation. And for good reason: it helps us figure out who is on our side or who is a competitor, which was, in the past, critical for group dynamics and survival. We make guesses about someone's feelings and motivations based on these subconscious reads of other's facial expressions, without even being aware of it.

- Our Leaky Tone. How you say something is as, if not more, important than the exact words being said. Think about it. You can say I love you with many different meanings depending on the tone, pitch, and cadence. And get this - infants sort everything they hear through the superior temporal sulcus (STS), but by 4 months, the only sounds that trigger the STS are human voices, especially when they carry emotion. But when we speak, the STS turns off. This is why our voice sounds so weird when we listen to it on a recording. And since we can only focus on one thing at a time, when we are talking we focus on our intention and the words we choose rather than the tone, pitch and cadence of our voice.

So, despite our best efforts to behave as we think we should, others will detect the incongruence between our behavior and our subterranean thoughts, feelings, and intentions.

It gets worse. There are 3 amplifiers that further widen the Gap between one person and another.

- Emotional contagion amplifier. When we are caught up in an emotion like anger, we almost always lose track of the impact our emotions on others. To us we are just mad, but others count the anger double and start assigning us the label of angry. We remember the thing that made us angry, while they remember the impact of our anger. I cannot tell you how many times my wife (and vice versa) has said, "Please stop yelling," when, from my perspective, my voice was only slightly elevated.

- Fundamental Attribution Error amplifier. Example - when I hop on a conference call five minutes late, you say I’m scatterbrained (character), whereas I say I was juggling five things at once (situation). We cut ourselves a break for our behavior by chalking it up to the situation, but we do the opposite with others, chalking it up to a character defect.

- Intention vs Impacts amplifier. Here we can have an outsized impact on others despite having good intentions like Andrew above. The cure for this is to separate intentions from impacts when discussing feedback. For Andrew it may look like this: “I’ve been working hard to be more patient [arrow 2 above, his intentions]. And yet it sounds like that’s not the impact I’m having [arrow 4 above]. That’s upsetting. Let’s figure out why.”

The end result of all of this is that we all, each of us, view ourselves in a generally positive light. We can:

- Judge ourselves by our intentions: “I was just trying to get the job done right!” This smells very similar to my sense above of needing to get shit done above.

- Attribute other’s reactions to their hypersensitivity - i.e. their character.

- Attribute other’s reactions to the context: “Look it was a tense situation, anyone would have reacted that way.”

And because we all collude to keep each other in the dark about these things, the person with the challenging behavior often goes unchecked, until it becomes a crisis.

Some tips to help us recognize our blind spots:

- Use Your Reaction As A Blind Spot Alert. When you find yourself thinking “What was their agenda?” or “What is wrong with them?” your next thought needs to be: I wonder if this feedback is sitting in my blind spot.

- Ask: How Do I Get In My Own Way? Do not ask general shit like: “How am I doing” or “Do you have any feedback for me?” Instead ask: “What do you see me doing, or failing to do, that is getting in my own way?” If you respond with genuine curiosity and appreciation, they’ll be able to paint you a picture that is clear, detailed, and useful. This takes serious ego strength.

- Look for Patterns. When you get feedback that stings, do not reach into your pockets and pull out past positive feedback that counters the current feedback. It is only an ego-protection move. Instead, take a breath, stay curious, and look for consistent feedback in two ways: First - are you both describing the same behavior but interpreting it differently. Second ask yourself where have you heard this before? Look for patterns.

- Get A Second Opinion. Start by framing it like this: “Here’s feedback I just got. It seems wrong. My first reaction is to reject it. But I wonder if this is feedback in a blind spot? Do you see me doing this sometimes, and if so, when? What impact do you see it having?” You must let your friend or colleague know you want honesty. In this circumstance you do not want a supportive mirror (reassurance) - you want an honest mirror, and you have to have the ego strength to deal with what you may not want to hear.

Once you have all this sorted out, you focus on change from the inside out, not the outside in. Andrew followed the outside-in path, and it failed. In my case, I genuinely felt that I wanted close relationships with my children and that I wanted them to feel psychologically safe enough to come to me with their problems. My intentions were aligned with my thoughts and feelings.

So I spent a lot of time and effort learning to just keep my mouth shut and to listen (actually really listen) and to imagine myself in their shoes and what their world might be like to them. I also learned how to frame notions about what they are going through by saying, "This is just a hypothesis, but ........... what do you think?" This has been magic in moving the conversation in the right direction with deeper understanding and connection. I try never to make any assumptions about what they may be thinking or feeling. Only hypotheses that they can refute or verify.

By revisiting my old 360, taking the "he is like an abusive boyfriend who you absolutely adore but can never be sure won't slap you" sentence seriously, I changed my life because I changed the depth and level of connection with not just my children, but with other people, at least to the extent that I can be aware of. It is, without question, one of the more impactful things I have done in my entire life, and it can be in yours too.