The Permanence of Impermanence

On Saturday, November 18th, 2023, I flew to Los Angeles, CA, to join my son Sam on a bike ride from LA to San Diego. I took my Moots bike to the Angry Catfish bike shop in Minneapolis, where they packed it up in a box that I took on my Delta flight to LA as a checked piece of luggage. My daughter Maya lives in LA and Sam and I met at her apartment to begin our ride on Sunday.

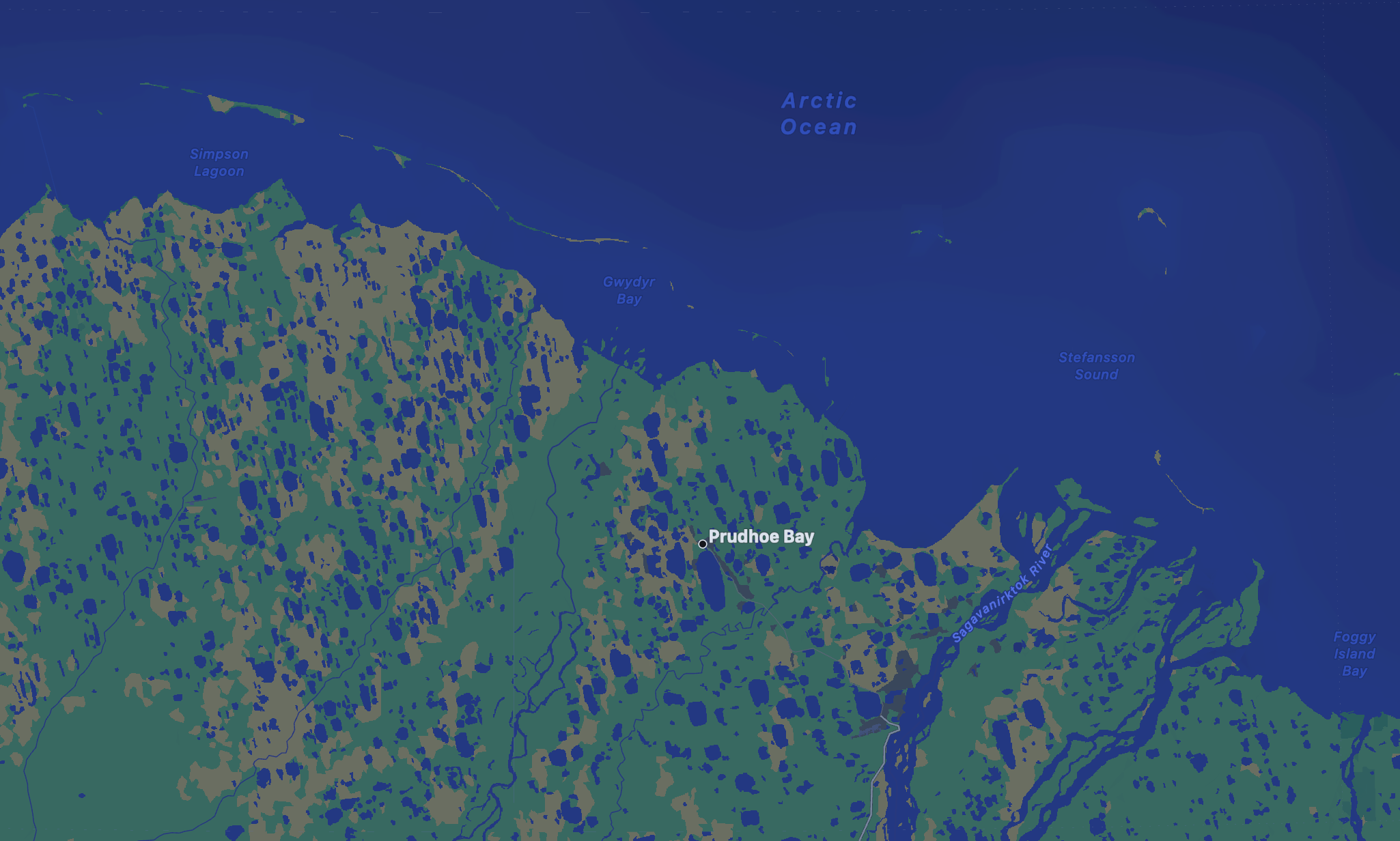

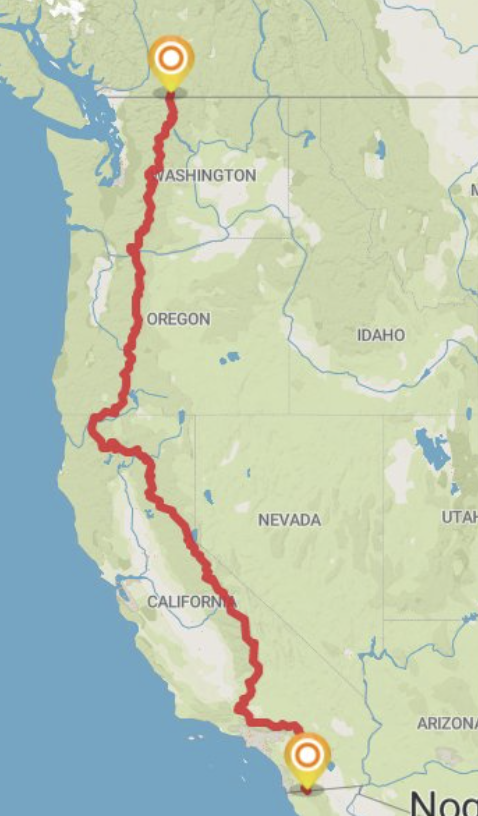

Sam had already started his ride 4 months and 4,000 miles earlier at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, and after our ride from LA to San Diego, he will continue on for another 12,000 miles to the southern tip of South America near the Antarctic. On a bicycle.

Oh, and Sam has a below-the-knee amputation.

I have never ridden a bike for more than 25 miles at a shot, so our plan was to ride about 40 - 50 miles a day for just 3 days. This post is not really about my part of the bike ride as it is, frankly, unremarkable. This post is what the bike ride represents to me, and to Sam, the evolution of our father-son relationship, and being a parent. Indulge me if you will.

Sam was born on August 23rd, 1993. Like all babies, he was a little blob of awareness ready to soak up the environment that fate had chosen for him.

Of course, part of that environment was/is me, and I relished tormenting Sam (and all 6 of my kids) whenever possible.

Sam grew into an introverted, warm-hearted, gentle boy who could be found seated on the floor in his bedroom with the door closed, pretending to fly his toy planes and dinosaurs in the air.

As time passed, other aspects of Sam's personality started to surface, especially around physical endeavors. He started swimming in 6th grade, and every morning before work, I drove him to practice at 6 am in the dark cold of our Minnesota January. I would never have done this at any age. Sam actually wanted to go, and he never, ever, complained.

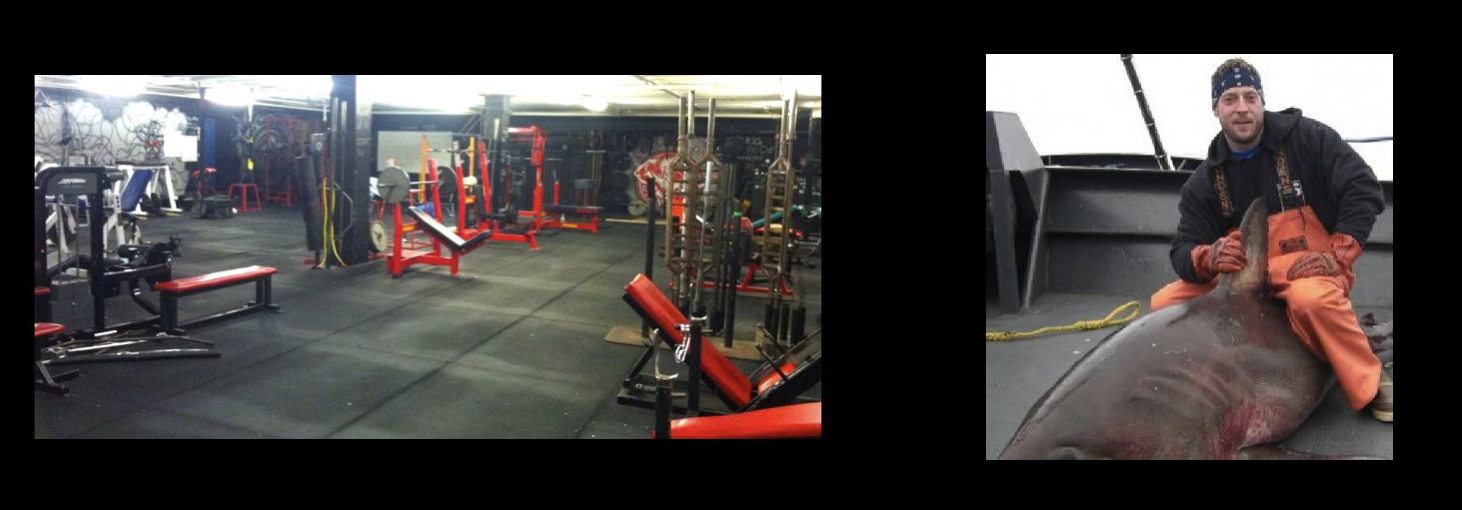

In high school, his physicality went nuclear. He swam for the high school team, went to State, and played football. He lifted weights at Los Campeones, a hardcore free weight gym in Minneapolis, with a trainer who noted: "Sam can take more punishment than anyone I have ever trained."

Then he met Shane VanDerBosch, a boxing teacher with both arms covered in tattoos and a black Chrysler Charger. Sam took lessons, and before long, boxing became so important to him that he moved to a dedicated boxing gym where his skills escalated, and where he started to have boxing matches that he routinely won.

Sam wanted to become a Navy Seal after high school. But my perspective was - why not the big prize - the Naval Academy, and then become a Seal? My influence helped push Sam to the Naval Academy, and in many ways, that project was more about me than what might have been best for Sam.

You see, I grew up in rather dire circumstances with an alcoholic, suicidal mother, and violent stepfather, and I was a juvenile delinquent (arrested 24 times, reform school 5 times), who had to drop out of high school and join the Navy to avoid prison. To me, the opportunity to go to the Naval Academy was a ticket to a life of endless opportunities.

As Anais Nin said: We don’t see things as they are. We see them as WE are.

It was a hard four years. Sam is a free-spirited soul who loves to travel to foreign lands and learn languages. He also lives in a state of what appears to me to be constant chaos. Ever since he was a boy, his stuff and his room were a total mess. him. Me, I like things tidy and to be able to find things. To me, mess is chaos. Sam was and still is genuinely okay with such chaos. It never bothered him.

In the book Dark Horse: Achieving Success Through the Pursuit of Fulfillment, Todd Rose defines what he calls The Standardization Covenant as the implicit agreement that if you follow the standard path - graduate high school, get into the best college possible, pick a career, maybe go to more school, and then climb the ladder, you will achieve success, usually defined by money or status. The potential problem? One can sacrifice their individuality for the sake of success as one does all of the "you should's" and "you need to's" of the Standardization Covenant.

I was a card-carrying member of the Standardization Covenant when Sam was a teenager in high school. Sam had two forces to battle on his way to creating his life for him: my perspective and influence, and the Standardization Covenant.

In 2011, at just 17 years old, Sam went to the Naval Academy. The Academy is difficult for everyone, but for Sam it was harder because, with its structure and culture, it was not a great fit for his personality. Sam's playful, relaxed, and spontaneous way of being (seen below in the picture) was the opposite of the seriousness and hierarchical structure of the Naval Academy.

In 2015, he graduated and became an Ensign, and then deployed to the Middle East as a surface warfare officer, where he led a team boarding vessels in the search for guns and people being smuggled to Yemen.

When he returned he bought a motorcycle.

I was at dinner with our daughter Maya in Boston when I got the call. A car hit the side of his motorcycle head-on, crushing his left lower leg. I flew out that night for what would turn out to be an 8-week stay. Four weeks in the hospital and 10 operations later, it became clear that amputation was the only option.

When he came to after surgery I was the one who told him that his leg needed to be cut off. There was nothing I could say or do to take the pain away. Losing a limb for anyone is devastating. For Sam, it felt like the end of his life, and it was the end of his life as he knew it.

The road ahead after surgery was very hard. Relentless problems with prosthetic fit, skin maceration and breakdown, and pain. Despite it all, Sam always found a way to go to the gym, even on crutches without his prosthesis, so he could work out. He started going to yoga classes. And he never complained.

After his discharge from the Navy, Sam was lost psychologically. With the loss of his leg, he lost his identity, and he thought he had lost his ability to do the physical things that brought him so much fulfillment. But it was challenging not only because he lost his leg. Between my influence and the Naval Academy, Sam never had the time and mental space to figure out who he really was, deep down inside.

I was also lost, as I did not have any of my usual surgical fix-it solutions for such a complex situation. All I could offer was time, patience, and the certainty that I and our family would be there for him, no matter what.

Our patience paid off. One night at dinner, Sam brought up the idea of hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, a 2,650-mile trail along the West Coast of the United States.

It was the first time in the 4 years since his amputation that I saw the spark and the boyish glint in his eye like the one in the picture of Sam marching above. But there was a problem. On some days, he could hardly walk more than a few blocks, and the project seemed impossible until he found Tilges.

Right in our backyard in Minneapolis is Tilges Orthotics and Prosthetics, a prosthetics lab with the most modern computer-based fitting process combined with a personal, caring, and tailored approach to each person and their physical goals. Tilges saved Sam, and they gave him his life back by enabling Sam to once again be the physical person he was destined to be.

Sam hiked the 2,650-mile trail through the heat of the desert and the snow and cold of the Sierra in 5.5 months, hiking an average of 15-20 miles a day - the average for people with two normal legs.

When Sam came home after the hike, he was a new person. Sam had truly found his path by hiking the PCT. As Sam said about being on the trail: "I felt like a kid keeping up with the other kids and playing. I don't think I recognized how much I missed that feeling and nature gave that back to me."

That is one of the great lessons I learned from Sam on our bike ride from LA to San Diego - the ability to be playful with living while being grounded in the reality that life is often very hard, because being a human being is hard. But we don't have to make it any harder than it is, and the art of not making it harder than necessary often comes down to a lighter touch with life itself.

Sam somehow keeps that light touch even in the winds of hardship that threaten to throw his mental well-being off course, like the first part of his journey in Alaska. He flew to Prudhoe Bay in July when there were 24 hours of daylight, when the bugs were as thick as a desert storm, where the dirt roads were wet and endlessly monotonous, and where he was alone, day after day.

Sam is now 30 years old. I am 69. Sam was in my world for the first 17 years of his life, and then in the Naval Academy, which in many ways, was an extension of my perspective and worldview. Now, for the first time, I was in Sam's world, following his lead. He put my bike together, made sure I was safe and led us to San Diego with me right behind him the whole way.

The rhythm of our short ride together allowed me to experience firsthand one of the magical things about Sam that I feel we could all use a lot more of in our lives. The perspective of playing like a kid in life, and not taking everything so seriously. His approach to the ride, to hiking the PCT, and in fact, the way Sam is about everything is to hold it lightly, not take it too seriously, and to let the trail of life take you where you should be, and to enjoy it, despite the ups and downs and the inevitable challenges.

I saw how he had to stop every ten miles or so to take his leg off and wring out the sock liner because it was soaked with sweat, and how the skin on the end of his amputation was sore and tender. I saw him limp after a day on the bike, and brush it off as just part of the deal. But most of all, I saw a man with a freedom of mind and a purpose who was "keeping up with the other kids and playing" again.

But there was more to Sam's resurrection. About a year ago, I apologized to Sam for not really seeing him for who he was, as an individual, when he was younger. I don't blame myself for not seeing him fully, as I, like all of us flawed humans, do the best we can at any given moment with what we have. But I have learned, and when I said I am sorry, all of the chains of the past were broken, and we were set free to meet each other fully, Sam for who he is, and me for who I am, and embrace and learn and experience and love each other, just because.

Sam drove me to the airport the Wednesday before Thanksgiving. I sat in the back of the van on an ice cooler, trying not to fall over. It was one of those bittersweet moments that are so hard but yet so beautiful - borne of my deep respect for what Sam has done and is doing, of the joy for our new relationship cemented by our short ride, and for the permanent nature of the relentless impermanence of life - highlighted by my age and not knowing when I will see him again.

But that is true for all of us. The permanence of impermanence is always in our face, and if we look at it straight on, and embrace it, and if we can see and value others for who they really are, life can be, as Sam said, "pretty sweet."

Here it all is in Sam's own words.